Part IV III: the Battle of Isandlwana

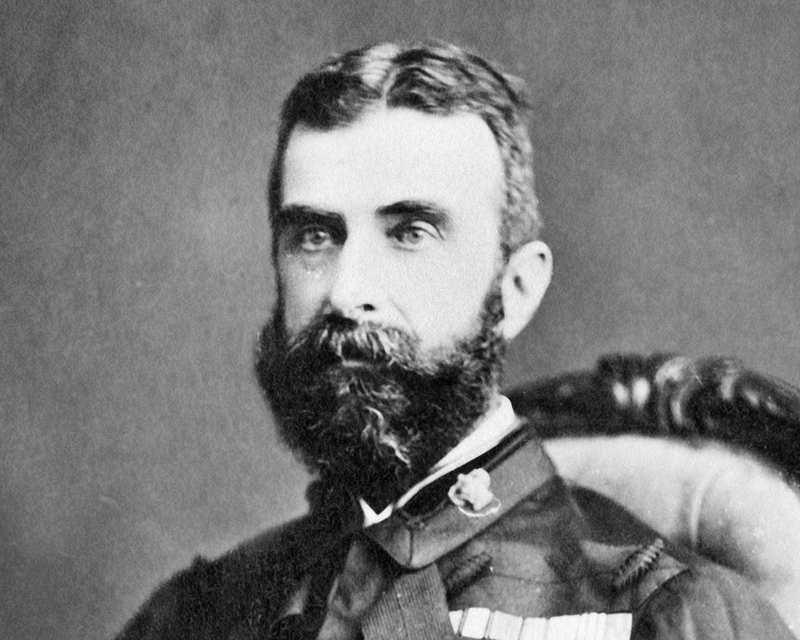

Lt. Col. Henry Pulleine was nearly 40 years old, yet had almost no combat experience before the Zulu War. Born, like the rest of his generation, in that awkward time for soldiers after Waterloo, he had proved himself a capable administrator in his years of service, and so Chelmsford felt fairly secure leaving the camp in his hands (it’s not like trouble was expected). Pulleine had the 1/24 battalion available, supported by two companies of NNC and two pieces of light artillery, to defend the camp. As the 2/24 marched out under the lord baron that morning, Pulleine was left to his own devices. He posted pickets atop the nearby ridgelines, had the men stand to, and then dismissed them to their breakfasts while he busied himself preparing to strike the camp and move on to Chelmsford’s position later that day or the next.

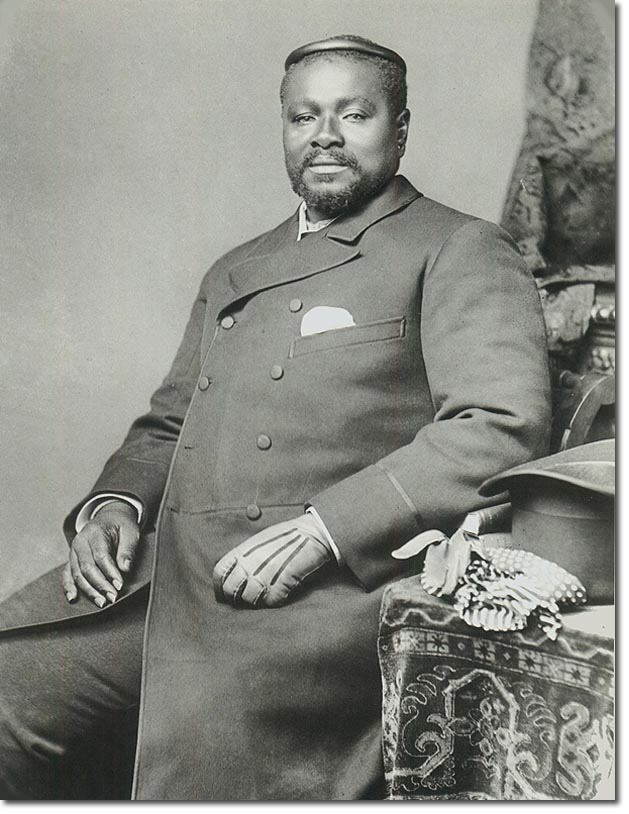

Back at Rorke’s Drift, at about 5:30 that morning a rider arrived from the column and delivered his message to Col. Anthony Durnford, commander of the II Column, charged with defending Natal against Zulu counteroffensives. Durnford, unlike Chelmsford or Pulleine, had long experience in Africa’s bush wars, and had raised a very effective mounted unit of blacks. He was a war hero, and had lost the use of his left arm in a fight against the Xhosa some years before. That had led to some abrasiveness in his relationship with the baron, who resented the younger man’s popularity amongst the frontier community. So, Chelmsford had stuck Durnford with the safe sideshow of guarding the border while he got all the glory of marching to Ulundi. Now, though, he called up II Column to reinforce the camp – the 500 men would do good service filling out the defenders in case of emergency. Durnford saddled up his men and moved out, unhampered by the unwieldy baggage train.

HIs arrival around 11 am was heralded by cheers and relief from the camp at Isandlwana, which had frankly been feeling rather abandoned after most of the fighting men had marched out. Durnford and Pulleine squabbled over who held command – Durnford, while senior, was also outside Pulleine’s chain of command in II Column, not III Column – but reports from the pickets atop the ridge to the north cut short that discussion. Hundreds of Zulu scouts and foragers had been seen milling about on the plateau to the north.

Both men were keenly aware of how exposed they were to the north – even from the top of Isandlwana, you can’t make out what’s going on on the Nqutu plateau – and were a bit anxious with all the army marching east and south. Durnford suspected that the activity might mean more amabutho lurking in the area, possibly intending to fall upon Chelmsford’s rear as he engaged the main impi. He resolved to take the initiative and put a stop to it, and ordered his men to ride out to the east and interpose themselves between the main army’s rear and any threat from the north. With Durnford was a little troop – 10 men – hauling experimental rockets, mostly useful only as psychological weapons. The colonel ordered the rocket troop to follow along behind him as best they could, dispatched two troops of riders to sweep the northern plateau, and then set off to the east.

Situation, approximately 11 am, 22 January

—

Chelmsford had a frustrating morning. His ‘relief column’ had arrived at Lonsdale’s bivouac after a two-hour march, only to find the commanders somewhat sheepishly reporting that the Zulus were gone. Irritated, he had set his men to beating the bush, hoping to flush the impi into the open for his decisive battle. Lonsdale, exhausted, gave his report and then set off to return to the main camp at Isandlwana.

A few scattered groups were seen – a hundred here, fifty there- and there were a few skirmishes in the morning, but nothing major. The visible Zulus withdrew to the east and the British pursued. By 9 am, Chelmsford himself had given up directing the action and settled down to breakfast, when a messenger arrived from Isandlwana reporting that large bodies of Zulu had been seen moving about north of camp. He dispatched a naval attache with a powerful telescope to spy out what could be seen of Isandlwana, 8-10 miles distant, but when the man reported that he could make out nothing other than that the cattle had been driven somewhat closer to camp, Chelmsford shrugged and had a nice breakfast with his officers. Soldiering – it was a good life!

The naval lieutenant would have stood atop the blue mountain at top center, looking west towards Isandlwana (out of frame to the right). The conical hill where the rocket battery is destroyed (spoilers!) is at center.

Breakfast finished, Chelmsford took his men back in hand and set them off in a flurry of orders to sweep the hills to the east some more, still seeking the Zulu. He also grabbed a man and ordered him to ride to Pulleine and get him started striking camp – this country seemed like a fine place for his next halt on the march. Just as the man rode off, another messenger galloped up in a flurry of dust. He handed Chelmsford a message: “For God’s sake come with all your men; the camp is surrounded and will be taken unless helped.” At the same time another messenger came to report that the Zulu were attacking Isandlwana in force.

Chelmsford was alarmed by this news – especially since one could now make out cannon fire, booming in the distance – but puzzled, too. Had he not left 1,000 men to guard the camp? Where was Durnford? 1500 rifles should be more than enough to see off any number of Zulu! He galloped to the top of a nearby hill and squinted back towards Isandlwana, the sphinx-shaped hill blue in the distance. He could see nothing from this distance.

The camp should have been able to take care of itself, but Chelmsford was starting to conclude that perhaps it had not been such a grand idea to split his army in half in enemy country, with the Zulu’s main strength at present still entirely unlocated. He gave orders and sent horsemen flying over the hils in various directions, trying to regather the column which had become massively scattered during the morning’s scouting. It took hours, but by about 3 pm, Chelmsford was regrouped and set off back towards Isandlwana, a march of 3-4 hours away.

As they marched, he met more desperate messengers, carrying unbelievable news: the camp had fallen! The Zulu had overrun it and were murdering anything that moved. Obvious nonsense – “I left a thousand men to guard the camp!” Chelmsford protested – but the next rider was not so easily dismissed: haggard, weary, and completely exhausted, Major Lonsdale himself, who had left Chelmsford that morning, came straggling in on a completely worn-down pony. He reported what he had seen with his own eyes, and confirmed that everyone’s fears were true:

Something terrible had happened at Isandlwana.

——

Ntshingwayo had kept his men closely under wraps the night of the 21st. While Chelmsford prepared to ride out to the southeast to reinforce Lonsdale and Dartnell, the impi had crouched in the ravine along the banks of the Ngwbini stream some distance to the north. No noise was made, no campfires were lit. A Zulu army could melt into the landscape when it wanted, and right now it very much wanted to lie doggo. They would wait out the 22nd – an inauspicious day for a battle, as it was a new moon – and attack at dawn on the 23rd, when the redcoats were strung out on the march.

But all armies, even Zulu armies, need to eat, and the Zulu carried no provisions with them. Food was instead supplied by foragers seizing cattle from nearby kraals and herding them back to the main force, so early in the morning on the 22nd small groups of these had slipped out to begin gathering in provision for the men. It was these foragers who had aroused Durnford’s suspicions upon his arrival at Isandlwana later that morning.

A group of boys had gotten their hands on a particularly juicy set of bovines and were urging them along the top of the Nqutu plateau, when over the crest rode one of Durnford’s scout troops, a small company of horsemen led by Lt. Raw. Raw and his men saw the meat on the hoof and the possibility of a bit of action (much better than dull guard duty on the Buffalo river!), and whooping, the horsemen swooped down on the boys.

Now, the top of the Nqutu plateau – all the land around Isandlwana, really – is wretchedly rocky and broken. The ground is strewn with boulders, rocks lurking in the tall grass capable of breaking a leg to the unwary runner or galloping horse. So, Raw and his men hardly rode like the wind, instead picking their way as rapidly as they could through the treacherous boulder fields towards the fleeing boys. The Zulu ‘little bees’ scampered away and dove over the lip of a ravine. Hard on their heels, Raw rode up – and halted.

In what I can only imagine was a supremely awkward moment, Raw looked down at 25,000 Zulu warriors, who were looking back at him, just as surprised. For a few frozen seconds, no one moved, then the nearest warriors starting shouting, “Usuthu!” – “Kill!” The war cry of the Zulu. Raw calmly summoned a rider, and asked him, “Please ride to Col. Pulleine. Tell him I’ve found the Zulu army.” Then the nearest Zulu were boiling up the ridge, the horsemen were racing back, and the battle of Isandlwana had begun.

Here the strength of the Zulu system showed itself. No one had planned this battle to start the way that it did, and no one gave orders. But the men knew they were discovered and that the chance of surprise was blown. So they attacked without orders – but not as a mindless horde. The amabutho began naturally falling into their various places in the system, the men dividing themselves without orders, already assuming the correct plan of attack. Thousands swarmed across the plateau and down its southeastern slopes – the left horn of the buffalo. Thousands more charged due west, across the top of the plateau, and down the broken terrain on the fair side before beginning to hook south – the right horn. And the majority went right over, straight to the crest, and then started pouring down upon the startled British on the hill below – the chest and the loins.

Raw and his men did not flee pell-mell back to camp. Instead, they executed a disciplined retreat – they would dismount, fire off a volley from their carbines, and then leap back on their horses to ride another 100-200 yards, reloading as they did. The Zulu were not suicidal beserkers, and every volley would drive their leading elements for cover on the ground. The camp was four miles distant – some say that the Zulu were able to cover that span in 20 minutes, others that it took closer to forty minutes or an hour. Regardless, for that hour, Raw and his men conducted a fighting retreat, carefully picking their way back through the boulder field – a horse stumbling now meant swift death (some men did stumble – and died).

Looking east towards the conical hill and Chelmsford’s distant scouting party.

Back at camp, men looked up from their card games or their meals at the sound of gunfire, up on the plateau. They knew cavalry had gone that way looking for Zulu a few hours ago, and they had pickets up there now. The firing did not die away, as one might expect in minor skirmishing, but continued and even grew in intensity. Soon enough a man came galloping into camp – “Zulu!” he shouted (duh) – and raced to Pulleine, who immediately sounded the alert. As drum rolls and bugles played, men sprang up, seizing their rifles and helmets, and began falling into line. Pulleine had them head out of camp a few hundred yards and line up on the lip of a small rise, to cover some dead ground and prevent the Zulu from taking advantage of it. The time was about noon.

East of camp, struggling through the difficult, boulder-strewn terrain, was the little rocket battery vainly trying to keep up with Durnford’s cavalry. They had just passed a small, cone-shaped hill when the left horn of the impi came sweeping down the plateau and around the hill. The miserable rocketeers, lonely and abandoned, had just enough time for a started volley before the amabutho swept over them, iKwla flashing.*

Durnford had heard the firing and had just about achieved his desired tactical position, that is between Chelmsford and any Zulu threat to his rear. Quite exactly what he expected to do with his 300-odd men against tens of thousands of Zulu, now that he had gotten there, is unclear, and Durnford didn’t wait around. As the left horn overran the rocket battery, Durnford found himself the only organized military force on the plain, and so he pitted his men against the Zulu. The horsemen fought the same way Raw’s troopers did – firing, then retreating, then firing again.

View north from camp towards the ridge the Zulu appeared on. Conical hill at right.

At camp, the line of redcoats forming outside it saw the pickets on the ridgeline before them suddenly open an intense fire. They didn’t last long before all the men atop the plateau were streaming down in pell-mell retreat – and then, hot on their heels, Zulu shields began appearing along the crest. The chest of the attack appeared, and after a pause to regroup from their long charge across the plateau, the Zulus descended to launch a frontal assault on Pulleine’s line.

The redcoats were not the famous “thin red line,” mind you. Chelmsford taking half the damn army with him had made that deployment impossible – the camp was too large for a tight grouping of soldiers. Instead, the British riflemen at Isandlwana fought in a loose skirmish order, a yard or two between every man, as the companies spread out to cover the gaps in the line left by the absence of so many of their fighting units. Now less than 1,000 of them opposed 20 times their number in Zulu warriors.

The Zulu’s view descending the plateau south towards Isandlwana.

Same view, January 2022

Still, morale was high. The Zulu descending the plateau were met by shellfire from the two field cannon, and crashing volleys from the Martini-Henrys of the 24th Regiment. A curtain of steel swept out around the British and cut down the Zulu. The amabutho went to cover, as any attempt to advance was met with a hail of rifle fire. On the left, the picket company – “A” Company, under Capt. Younghusband – made their way down from the plateau and onto the slopes of Isandlwana itself. In the center, the British line extended from west to east a few hundred yards, before bending to the south to cover the camp. Durnford was still invisible, out on the plain, trying his damndest to slow down the left horn, which had yet to appear to the main camp.

Troopers laughed and joked about the good day’s hunting, their initial shock wearing off as they saw that their rifles could indeed ward off the Zulus. By half twelve, the situation seemed stable – the main Zulu attack was pinned down north of camp along the base of the plateau, Durnford was holding off the left horn over on the British right. Around this time the messenger from Chelmsford arrived, instructing Pulleine to strike the camp and prepare to join him out east. Pulleine felt comfortable enough to reply, “”Heavy firing to left of our camp. Cannot move camp at present. Shepstone has come in for reinforcements and reports the Basutos [Raw and Roberts horse] are falling back. The whole force at camp turned out and fighting about a mile to left flank.” It was the last message he would send.

Up on the Nqutu plateau, Ntshingwayo exercised what control he could over a battle he had not intended to fight. From his position atop the ridgeline he could see the entire battle spread out below him – the amabutho in the center working their way towards the British firing line, taking advantage of every gully and crack in the ground for cover, over on the left his warriors driving the heavily outnumbered Durnford before them. Vainly the Zulu commander urged his men via gesture and runner to shift to the left, to outflank the redcoats and storm the camp from its open right flank, which was dangling in the air, apart from Durnford’s cavalry.

View from British camp to the east, where their left flank is in the air. Note the cairns…

The troopers under the one-armed colonel by now were back across the plain and tumbling into a big donga that ran near camp on the British right. It was a solid position from which to fight, and for a while their volleys again checked the Zulu left horn. Everything still seemed under control – but the British were unknowingly on the edge of catastrophe.

The standard British rifleman was typically issued 70 rounds of ammunition. Further issues of rounds were made from regimental ammunition wagons, stationed behind the lines or in camp. In the years after the disaster, some would allege that at Isandlwana this supply broke down – overly stingy quartermasters refused to issue bullets to any but their own companies, or that the lids on the boxes were screwed on too tightly. Later battlefield archaeology has shown most of these rumors to be false – with one exception: Durnford’s cavalry, holding the British right.

The big donga Durnford’s men were making their stand in was a solid half-mile or more from the camp. The left horn was pressing them closely, and the troopers had been fighting now for hours across the plain. Men were nervously patting their pockets, checking with their mates to see if they had any rounds to spare, and looking expectantly towards the colonel: ammunition was running out.

Durnford dispatched two troopers back to ride like hell to camp and round up some crates of cartridges. The two tore across the plain back to the slopes of Isandlwana – but then, chaos. See, Durnford had ridden up just that morning from Rorke’s Drift, and hadn’t much bothered about his supply train as he did so. The southern part of the camp was given over to a vast wagon park (the laager Chelmsford had refused to make), and now II Column’s supplies were hopelessly snarled in it. The first quartermasters the troopers found flat refused to give them any more rounds – those were the 24th’s, they would have to find their own. Helplessly, they scoured the vast tangle of wagons searching for their own – but by the time they were at last successful, it was too late.

As the steady volleys of fire from Durnford’s donga sputtered to a close, the men in the leading amabutho of the left horn sensed the change. The Zulu began to press more closely – some still fell, but much more sporadically. Within moments, the entire horn was once more in full charge, and Durnford decided to call a retreat.

Situation, 12:30, as Durnford retreats.

II Column’s retreat back towards the camp and ammunition opened up the British right flank to attack. The Zulu swarmed forward, taking the too-extended British skirmish line in the flank, iKwla flashing, and Pulleine realized his men were too far out. He issued orders for the entire line to fall back towards the camp, to reform a tighter defense there – but the Zulu were not fools. As the British troopers ceased fire and began to retire, the warriors leapt up from their covered places and charged after them. What ensued was a foot race back to the camp, the Zulu running like hell to get in among the British before they could re-establish their deadly curtain of rifle fire. Pandemonium ensued.

The neat lines of the 24th dissolved as Zulu and redcoat together came in among the tents. The imperial soldiers were reduced to fighting in isolated knots with bayonets as the Zulu swarmed around them. Many men fell on the run, never able to get back to the camp. Others did so, and gradually company squares started to form here and there. But it was already too late – the British were doomed. Some men tripped over anchor lines on the tents – any fall being met with swift death. Others backed up against the canvas walls, defending themselves until Zulu crept through the tents and slashed their way out the back. Drovers, cooks, stewards raced here and there, falling and dying as the wave of amabutho swept over the encampment.

The cairns that still stand today on the slopes of Isandlwana mark the places where British soldiers lie, buried where they fell. Pulleine, observing the disaster of what was the only battle he’d ever fight, ordered two subalterns, Lts. Melville and Coghill, to escape with the regimental colors, then by all surviving accounts retired to his tent, where he met his fate. Entire companies dissolved and were massacred as the Zulu fought their way through the camp.

Two patches of organized resistance remained – on the left, Capt. Younghusband’s A company withdrew across the shoulder of Isandlwana in good order, fending the Zulus off and making their way towards the southeastern corner of the hill. On the right, Durnford’s troopers provided a rallying point and many redcoats gathered around the one-armed colonel, who made a stand on the saddle just south of Isandlwana. As terrified teamsters, camp followers, NNC, and other hangers-on streamed past him to the south, it looked for a few heartbeats like Durnford might be able to make a stand and shield the retreat of a good portion of the British force.

Then the right horn arrived.

The Zulu right had made a wide swing through the hills to the west as the battle had progressed, all the way around the far side of Isandlwana. It had taken ages, but now thousands of fresh warriors poured right in at the British rear, cutting off all retreat. Durnford and his men formed one last square, surrounded and shrinking as men fell to thrown assegais or to random Zulu rifle fire**. Durnford himself was visible to the end, haranguing and encouraging his men, before falling himself to a Zulu bullet. Then the final rush came and overwhelmed the last few dozen survivors.

Durnford’s cairn, on the saddle just south of Isandlwana. Younghusband’s A company fought on the hill itself at top-center.

Up on the hill, Younghusband’s A company ran out of room to retreat as the right horn swept over the hill behind them. The Zulu report that, as the British fixed bayonets and prepared for a last stand, the inDuna (that is, a Zulu officer in charge of an amabutho) halted his men and allowed the British to prepare themselves for one last honorable fight. Younghusband sheathed his sword, and proceeded down the line of his survivors, offering each man his hand in turn and thanking them for their service. His farewells given, the British resolved to die like imperial soldiers and charged the Zulus with a roar. The fight was swiftly over.

At about 3:00 in the afternoon of the 22nd, a solar eclipse swept over the ruins of the British camp. The only living things in the camp were the Zulu warriors, who roamed around the tents and carriages, looting and pillaging, celebrating their great victory over the invaders of their country. To the southwest, panicked survivors, hotly pursued by the Zulu, fled down a ravine towards the nearest practicable ford in the Buffalo – to this day known as Fugitive’s Drift. There were no redcoats among them – the men of the 24th had died in their places. More than 1300 of the defenders died – 800 redcoats and sundry other camp followers, NNC, cavalry, etc. The Zulu dead are estimated to be about 1,000.

Lts. Melville and Coghill, with the colors, fled down this ravine with the Zulu hot on their heels and splashed across the river, which was running high. Melville fell from his horse in the difficult crossing, losing the colors. Coghill, safe on the opposite bank, threw himself back into the river and pulled his companion to safety – but in the process was wounded by a Zulu bullet fired from the far bank. The two men struggled onto the Natal side of the river and collapsed, Melville refusing to leave the injured Coghill’s side. The Zulu came upon them there and both men were killed. The colors were recovered from the river a few days later.

All told, a handful of whites – about 74 – managed to flee down the ravine and escape at Fugitive’s Drift. No one bothered to count the amount of NNC troopers who escaped that way, but it was some hundreds, as well as many of Durnford’s troopers. Among them was Lt. Raw, who had fought the Zulu all the way from the Nqutu plateau, across the plain of Isandlwana, and then escaped. He was one of only 5 British officers to survive the day.

The memorial to the Zulu dead takes the form of an honorary leopard tooth necklace, awarded to a warrior who showed bravery in defense of his people. The arms of the necklace mimic the horns of the buffalo encircling the British invaders on the hill above.

As night fell, the Zulu amabutho finished their looting and dispersed. It wasn’t until after dark when Chelmsford’s column came straggling over the plains. Zululand is dark at night, in a way that is difficult for those of us who live with constant electric light to appreciate. There was no moon and it was impossible to see more than a few feet. Chelmsford had his men camp in the ruins of the wagon park, unwittingly surrounded by the mutilated corpses of their comrades, and forbade anyone to leave camp – ostensibly due to the danger of attack, but more likely to prevent the harm to morale that would ensue from the men discovering the horrible fate of half the army. Chelmsford himself rode to the shoulder of Isandlwana and looked out to the west.

In the distance, he could see a red glow on the horizon.

Rorke’s Drift was burning.

Chelmsford’s view of Rorke’s drift from the shoulder of Isandlwana. The mission station is just behind the small hill at center.

*Amazingly, 3 survived by playing dead.

** The Zulu had been importing guns for decades, but didn’t use them in any organized fashion. Mostly they were used for harassing and skirmishing fire, the arm of decision was still the iKwla-armed regular infantry.