This post has been a passion project of mine for about 6 weeks now.

See, I’ve heard it often said that American schools are failing, and that we could learn a lot from the way places like, say, Korea*. I think that’s wrong for a number of reasons.

First, it’s all but impossible to make generalizations about the entire American school system. American schools are organized on a district-by-district basis, educate literally tens of millions of students, and are spread across an entire continent in a wildly diverse array of towns, cities, landscapes, economies, cultures, races, religions, and so on. There is no “typical” American school. Do you take the private prep school in Connecticut as an example, or the tribal reservation school in Montana? The massive Los Angeles high school, or the little rural Mississippi schoolhouse?

No, American schools have to be taken on a case-by-case basis. My own experience is hardly the most extensive, but I’ve had the privilege to work alongside some brilliant educators in a great district at Clayton (shout out to Deb, Aimee [both Aimees], Richard, Barry, Josh, Jo, Mel, Spencer, Heather, Susan, Chris, Dave, Rob, Kate, Stephanie, Julie, Sarah, Mike, Paul, AnnMarie, Mark, Cassie, April, Erin, Jennifer, Caitlin, and others – let me take a moment to say that I admire each and every one of you individually, from your talent in the classroom to the love and enthusiasm you bring to your work each day. Having the opportunity to work and learn alongside all of you was one of the greatest blessings of my life. Keep it up), and I’ve also worked at some not-so-great schools. So, there is no “American” school that we can point to as representing all of American education.

Second, I don’t think Korean education is a system we necessarily want to import. It might work for Koreans, but not for us.

Let me explain.

Why Korean Schools are Not American Schools

The Korean education system is widely touted as one of the best in the world. Korean students’ high achievement scores in math and literacy are often cited as showing the superiority of the Korean way, and as an indictment of countries with lower average scores (most often the USA).

Everything that follows is based on my own personal observations and opinions and should be in no way treated as authoritative – but if you want a view from the Korean trenches it may serve.

The bottom line is I think there’s something to the stereotypical view – Korea has certain cultural and institutional advantages, and its education system is practically designed to achieve good test scores. However, I also think that a focus on test scores alone masks a lot of serious problems with Korean education, and I am not at all convinced that the system is the best means of preparing Korea’s young citizens to face the future.

——-

Korea’s Cultural Advantages

It’s very important to understand that Korea is not like the US. I have no doubt that many of you are reading this now and either snorting or rolling your eyes at an obvious assertion, but I just want you to pause and appreciate it for a moment: Korea is not the US. We understand that intellectually, but that has important consequences on the cultural level.

The main thing is Korea’s Confucian culture. Confucian ethics heavily emphasize duty, responsibility, and hierarchy. Sons have a duty to respect, honor, and obey their fathers. Fathers in turn have a duty to defend and provide for their sons. The Korean worldview (which is shifting somewhat as Korea integrates with the modern, largely-Western world) neatly places everyone into their place into the hierarchy: Parents over children, elders over the young, men over women, etc. Now, individualist Western sensibilities chafe at this, but it’s important to note that Koreans are fully aware that the West does things differently, but they don’t really care. The way they do things is perfectly natural and works well for them. They view us the same way we view them.

So, most people (not all – just as there are Westerners that want to promote more communal ethics over our own individualist ethos, there are Koreans who want to make their own society less communal) are perfectly comfortable in this system. This sense of heirarchy is everywhere. Young people I’ve never met before are unfailingly polite and respectful, both from my status as an elder (I’m only 30! I’m not old) and as a teacher (when they know I’m a teacher, which is a fair guess when you see a Westerner here – probably an English teacher). Young people are socialized their entire lives to obey their parents and their teachers.

Now, what do those parents and teachers want them to do? To learn. Education is almost holy to Koreans. Everyone here respects and honors getting a good education. Top to bottom, from the President all the way down, the message is universal: you must get a good education and go to a good university. Korea is an extremely proud and patriotic nation, and one of their badges of honor is their educational attainment. It is every students’ duty to uphold that and contribute to Korea’s continuing dominance in the world rankings (they especially need to keep ahead of the hated Japanese).

These two factors – Koreans’ respect for elders/teachers, and the society-wide veneration of education – means Korean schools have an influence over Korean students to a degree Western teachers can only dream about. Seriously, I used to teach middle school in the USA, and the difference is night and day. Student behavior here is an absolute dream and it’ll be hard for me to go back to the, uh, livelier environment of an American middle school. The result of this school power is that schools can ask a lot more of Korean students than American schools do. If Americans tried some of the things I’m about to tell you, well, they’d not only have students but parents also revolting. They’d never get away with it. But in Korea, parents will – almost – always support the teachers over the students.

The Korean school system – an overview

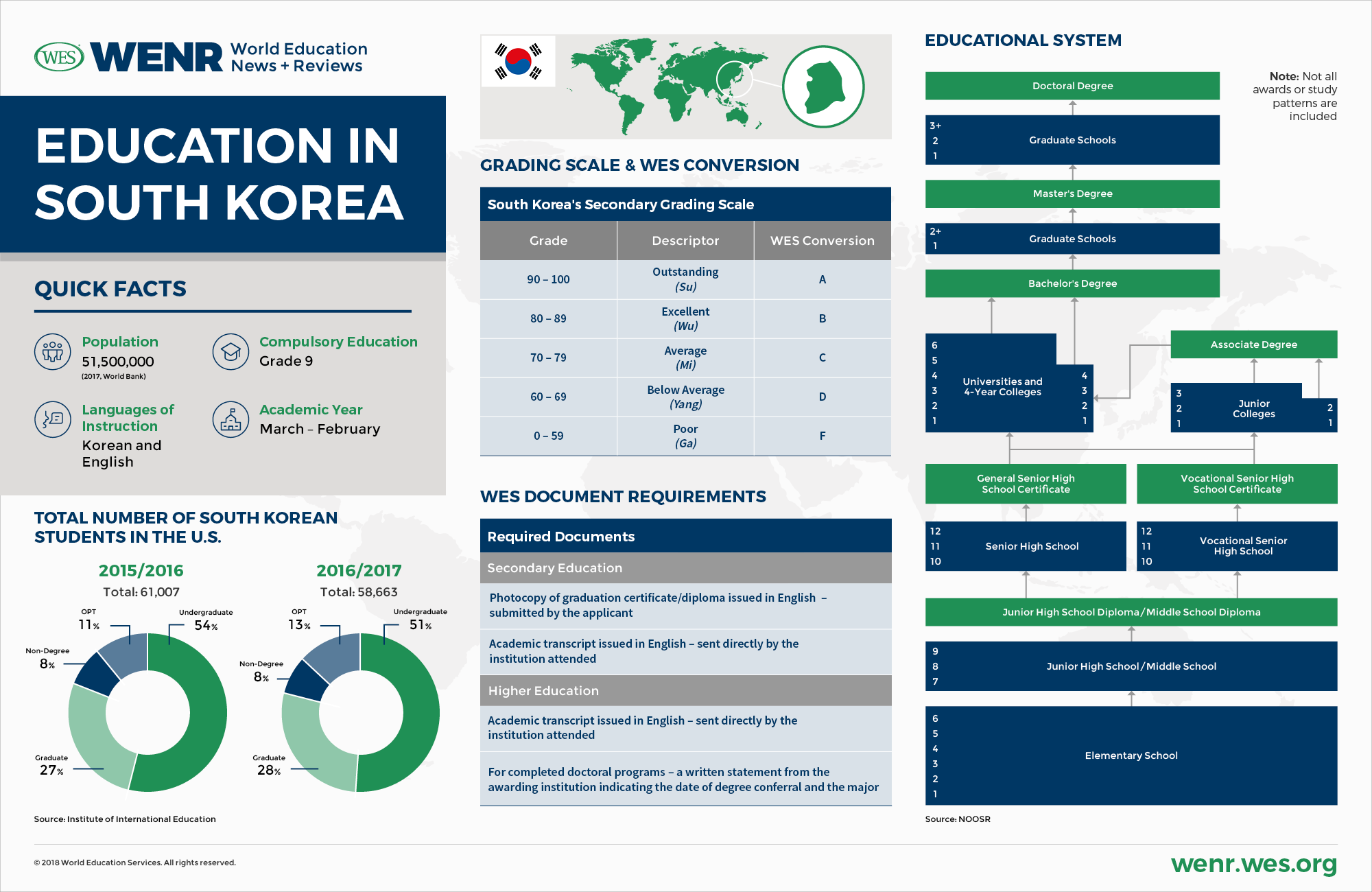

Korean schools are modelled after the US system, due to the long-standing presence of American troops and the accompanying bleed-through of US culture in the country. Students attend 6 mandatory years of elementary school and 6 years of secondary, split between 3 years of mandatory middle school and 3 years of “optional” high school. High school, while neither mandatory nor free, is basically universal among Koreans due to the society’s intense focus on educational achievement.

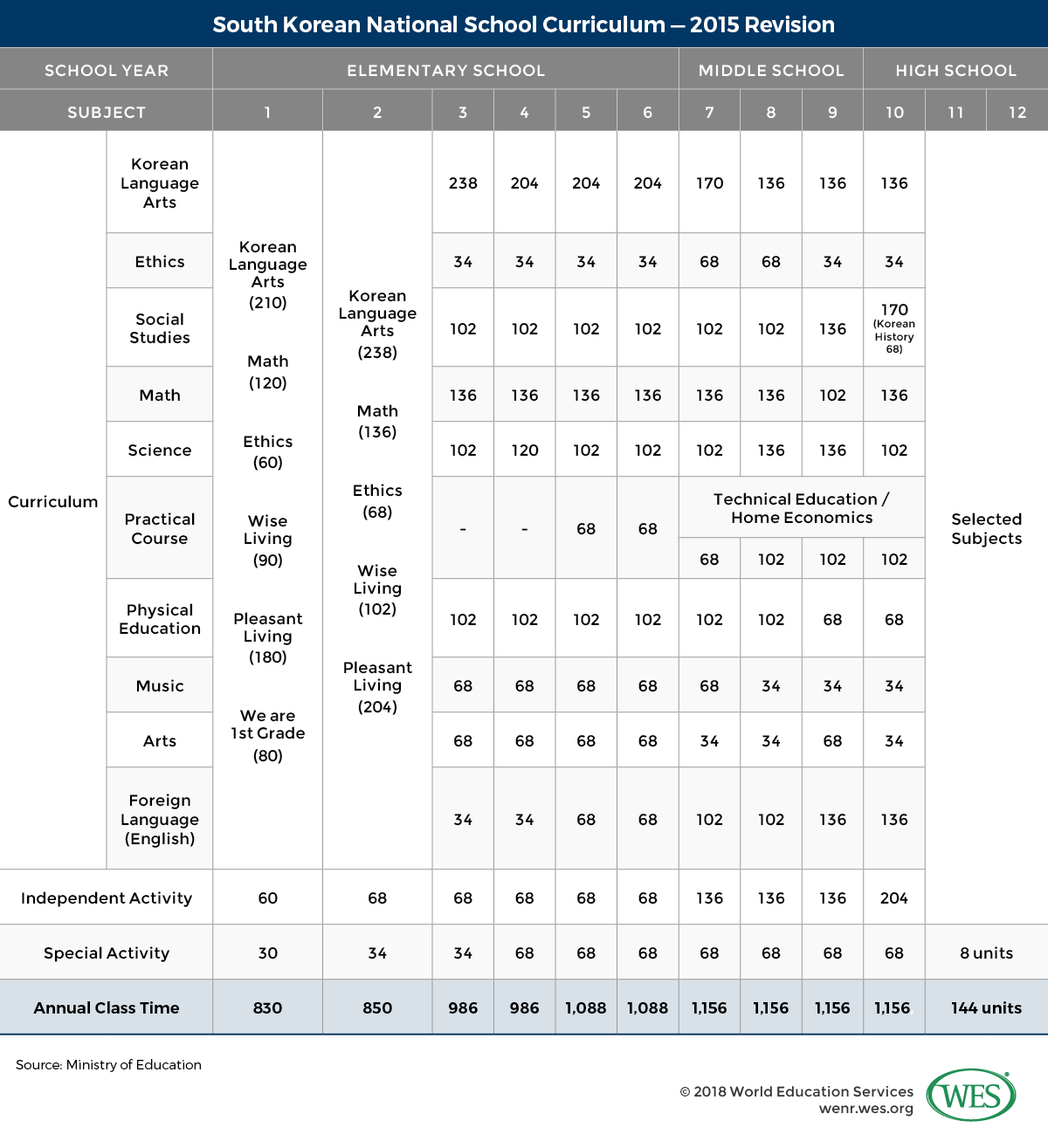

Students learn math, science, “life skills” like pro-social behavior, and, starting in 3rd grade, English, history, and other “soft” subjects in elementary school. Middle school is more of the same, with an increasing focus on English, math, and science. High schools are split into general academic subjects (about ¾ of students), “vocational” schools (about ⅕), and specialized private prep schools (like the one I teach at).

English proficiency is an obsession with the country. The language is mandatory starting in 3rd grade, and the Korean government is heavily focused on promoting competent English education, including paying its own teachers to live for extended periods of time in English-speaking countries and offering native English speakers very generous contracts indeed to come over and teach their own students (now you know why I’m here). Many high schools and universities are taught exclusively in English. In addition, there are possibly thousands of private English academies in the country – I pass posters and ads for them all the time.

All of this is aimed at the big event: the CSAT. This event, held in November every year, is THE college admission test in Korea. The results of this single test is the highest of high stakes for Korean students – just short of life or death (actually, given the suicide rate, for many students it IS literally life or death). Traffic shuts down and the government runs extra busses and subways to make sure students make it to the test on time. Air traffic over Korea is shut down for the 8 hours the listening portion of the test takes place in.

The baseline for admission to Korea’s top three universities (Seoul University, Korea University, and Yonsei University, “SKY”) is a near-perfect score.

Tailor-made for tests

The result of all this is intense, even insane competition amongst Korean students. No reputable job will look twice at them if they fail to have a degree from a top university. Worse, their friends, their family – everyone will be disappointed in them if they fail. In the heavily Confucian culture of the country, this is an almost unbearable shame. It’s difficult for Westerners, at least those of us from guilt cultures like America, to empathize, but imagine how your family would look at you if they knew you, I don’t know, hosted dog-fighting rings for fun or had a huge stash of kiddy porn. Well, maybe not that extreme, but you get the idea. Failure is unthinkable.

But for many students, failure is inevitable. There are millions of students jostling for a very limited selection of spots. There’s no way for all of them to get in. The result, then, is an arms race. Private schools, tutors, hours upon hours of study – any edge students, and especially parents, can find for their kids, they take, starting as early as elementary school. Anything less results in your child falling behind, and that is doom.

Most schools know this, and respond. Korean education is very grade-focused, and the reputation of drill-drill-drill, rote-memorization is, while a bit exaggerated, not entirely inaccurate. Schools demand perfection in memorization and recital, whether of math facts, of complicate chemical equations, or a massive list of English idioms for some goddamn reason (I still don’t get that last one). I once was called in and chastised by my principal because my students were averaging scores of 90 on my tests and I needed to get that down to 80.

So, all of Korean education is optimized around students delivering the best score they possibly can on a single standardized test at the culmination of their academic career. Their entire culture, society – the whole support network students have access to is dedicated to this one goal. Thus, of course you get a system that is very, very good at churning out students that will score well on standardized tests!

But all that optimization comes at a high price.

Costs

Let’s talk about my own personal experience. I teach English at a gifted high school – and right there was my first cultural shock. A gifted high school would never fly in the United States. Why not is left as an exercise for the reader. For my part, it’s a dream job. I only have 3 or 4 total preps a week (barely 20% of my middle school preps), the administration is supportive, and the students not only are imbued the Korean spirit of subordination and respect, but also are motivated, talented, and proud of earning their place at the school. That makes instruction a breeze – behavior problems are totally absent from the school and I can focus solely on providing content. I’m not a babysitter here. In fact, the only trouble I ever have with students is one common problem: They sleep in class.

Big deal, you think. They’re teenagers. Teenagers sleep in class all the time. And you’re right! They do! In this way they are no dfferent than American teenagers.

But the way Korean students sleep is different than American students. The students shuffle in at the start of class, take their seats while waiting for the bell to ring, and immediately nod off. Some will sleep until the bell rings, then do their best to stay attentive through the lesson. Others – well, not so much. They remind me of nothing so much of stories I’ve read of soldiers in combat zones, who quickly master the art of sleeping whenever they have a spare moment. They resemble veterans in other ways – Korea’s suicide rate is the highest in the OECD, and suicide is the leading cause of death among Korean teenagers. The most commonly cited reason? Academic stress.

No wonder, either. Here’s my students’ biweekly schedule.

At 7:30, wake-up music blasts through the dormitory (I was allowed to set the playlist during Halloween week, and you bet your ass I scheduled all the spooky music I could. Halloween isn’t really a thing here, but it’s my favorite holiday so by God I’m making it a thing). The students must all rise from their beds and report to a check-in desk, which will note that all students are awake and up. If a student fails to check in, a teacher will be sent to investigate.

By 8:00, all students are out of the dorms. They can go to the mess hall for breakfast, if they like. Breakfast is typical fare – rice, some sort of fish soup, kimchi. The same food they’ll eat for lunch, and for dinner.

8:20, and they need to report to home room. Many students have opted to skip breakfast so they have more free time, so they will straggle in from all over campus. Following 20 minutes of home room, the school day begins – 50 minute classes with 10 minute passing periods, plus a lunch period. No individualized classes here – they move with the same group all day. The ~16 people in their home room will be their main companions for the entire academic year.

At 4:20, the final class ends and it’s time to clean the school. They scatter to the various rooms, dig out cleaning implements from various cupboards built for the purpose, and swiftly sweep, take out the trash, dust, etc.

4:40 and their “special after school club” begins. Basically this is another class – math, physics, chemistry, some subject that they selected. You choose at the beginning of the year and, of course, cannot switch. Many have said that their biggest regret at school was choosing the wrong club.

At 6:00, it’s time for dinner. Same stuff as lunch – rice, fish soup, kimchi, some form of meat dish usually. Same as breakfast will be in the morning.

At 7:00, it is time for “self-study.” Self-study consists of the students gathering in a large study hall filled with individual study cubicles. They will set up, each in their own cubicle, and spend the next two hours hitting the books.

At 9:00, they get a break.

At 9:20, self-study resumes. Another two hours. Same as the first. Some admit they have difficulty concentrating at this time.

At midnight, the dorms are at last unlocked. The students are allowed to return to their rooms and to sleep. Most don’t, of course. They have been unable to socialize outside of mealtimes literally all day, so most stay up for one to three hours talking with their friends and visiting. It is their only free time during the day. Most go to bed around three am.

Four and a half hours later, the morning music blasts again and it resumes.

Saturdays, there are no classes. Instead, students spend the morning at a special club – maybe sports, if they were smart enough to sign up for baseball or badminton or soccer – or else writing, art, music, one of the finer arts. In the afternoon, after lunch, self-study time resumes. This will last in 4-hour sessions, with breaks and a meal, until bedtime.

Sunday, they have self-study in the morning, and then the afternoon is free.

Every other weekend, they are allowed to visit home.

Now, my high school is an intensive, elite high school dedicated to training Korea’s gifted and talented children in the ways of science. Surely normal high schoolers don’t have it so bad, you’d think? And you’d be right! …sort of.

Not all high schools are boarding schools (although many are). And no elementary or middle schools are. However, such is Korea’s intense focus on education, and such is parents’ obsessive competition to get their children into a top university, that letting your kid only study at school is for fools and beggars. Everyone else ponies up for private tutoring, most commonly hagwons.

Every expat teacher in Korea knows hagwon horror stories. These soulless institutions crouch inside virtually every Korean office block, gaudy advertisements outside blaring that they will give hopeful parents’ kids a leg up in math, in science, in English. And some of them do! But many are exploitative babysitting mills, hoovering up guileless parents’ cash and shoving kids into bleak rooms lit by dim rows of fluourescent bulbs being taught by an underpaid foreign teacher (who may not even be in the country legally and so is unable to complain to the government about poor treatment).

Hagwons, to my mind, illustrate a potential failure of private school choice, which I otherwise support. Parents find it very difficult to judge quality, and besides are often unable to afford better even if they know it’s not the most ideal circumstance for their kids. But they feel they have no choice, because if they pull little Kim Hwang-Ju out, how will he ever get into a good high school? And if he fails to get into a good high school, what chance does he have at university? You’d basically be throwing his life prospects into the fireplace if you did that. There’s an aching, roaring demand for private tutoring in this country, anything at all to give your kids a leg up on those bastards’ devilspawn next door, and hagwons are a parastic entity come to fill the void. Some may be legitimate, run by scrupulous employers and offering quality education – maybe even a majority! But there’s also plenty of profiteers out to grift parents.

Anyway, kids outside the gifted high school may go home at night, but it’s just long enough for dinner or so. Then it’s off to the hagwon, where they will stay until 10:00. It used to be later, but the government cracked down and installed a curfew on students – with the result that many underground late-night hagwons exist.

The point of all this is that Korean education is a relentless, ruthless, remorseless grind. Students are under tremendous pressure from their families, their peers, and all of society to succeed, with total shame being visited on any who fail to keep up. The school system has developed into an authoritarian monster bent on packing every last moment of the students’ day with more study! More education! More knowledge! With the entire focus bent on a few standardized tests – not tests mandated by the government, mind, but by the universities. You have to pass a difficult entrance exam to get into a good high school. And a good high school which focuses single-mindedly on preparing students for the single national college entrance exam is the only way you have prayer of making it through the brutally competitive college admissions process.

It’s important to note that the Korean government is aware of many of these problems, and President Moon Jae-In’s administration is working to correct them (making high school admission more equitable, trying to find jobs for college graduates, trying to improve students’ life satisfaction so they stop killing themselves, fighting the hagwons). But everyone here knows how difficult it is for a government to fight cultural inertia, and Korea’s educational system is not the result so much of deliberate government design as it is the natural consequence of a set of cultural imperatives. So, President Moon’s efforts have not met with universal success.

So yes, Korean students get good test scores. With all this, it’d be completely astonishing if they failed to be one of the top nations in the world when it comes to test scores. But I am increasingly left with the feeling that that’s all they have: test scores. And what good are test scores, in and of themselves? Tests are only good insofar as they measure something real, and to my mind the only real thing Korean national tests measure is students’ ability to optimize for the tests. Are Koreans more innovative than the rest of the world? Do the best Koreans outcompete the best Americans, or the best Germans, or the best Israelis, when it comes to scientific breakthroughs, to new tech start-ups, to powering the innovative and creative information economy of the future? I’m not so sure.

The Korean economy, which rapidly grew from the 1980’s, has been slowing down in recent years. Korea’s unemployment rate among college graduates is extremely high. With virtually every young person pursuing a degree, naturally degrees have become devalued by many companies. Perversely, the ferocious competition to get into college to get a good job has resulted in getting into college no longer guaranteeing a good job. Observers have noted that Korea’s students often seem narrowly focused, have difficulties taking initiative, and lack the flexibility needed for the modern economy. At the same time, vocational training is way down (much as in the US) and many “blue collar” jobs go unfilled here because of the extreme social stigma from not getting a college degree (and consequentially being overqualified to be a “mere” plumber or electrician).

I don’t want to say that the Korean education system is a failure. It’s not. Korea has one of the highest rates of literacy in the world and one of the highest rates of tertiary education in the world. Korea has grown from abject dirt poverty in 1953 to one of the 10 largest economies in the world today, while stuck on a tiny, resource-poor peninsula wedged between the devil and the deep blue sea (the People’s Republic of China and Korea’s hereditary enemy, Japan). Many great and popular brands are Korean – Samsung, LG, Hyundai, Kia – and Seoul is one of the greatest cities in the world. The Koreans are probably the best-educated national group in the world and they have a lot to be proud of. But that success comes at a high price. And in my opinion, having worked in it, is that their system is one that is neither capable nor desirable of being emulated elsewhere.

Tl;dr: Yes, Korea has great test scores, but don’t read too much into that.

*I really have come around to calling it Korea instead of South Korea. It’s one nation that’s presently in a state of civil war, and has been for the last 70 years. Both governments claim sovereignty over the whole peninsula, so it’s not like there’s an official North Korea and South Korea. There’s one Korea, and which government is the legitimate one is, well, open to disputation. Personally, I back the regime that’s not a murderous Communist dictatorship.