Part VI. The Aftermath

Ten days after it had left camp, Redvers Buller’s army staggered back into Springfield. It had lost more than 10% of its strength and was no closer to Ladysmith than when it started. The Boer line on the Tugela looked as unbreachable as ever.

But events were already in motion elsewhere that would render Spion Kop, and all the blood and sacrifice made for the hill, irrelevant. Over on the western front, Lord Roberts, his Chief of Staff Kitchener, and 30,000 very irate British soldiers were prepared to settle the business once and for all. Within two weeks of the failure of Bullers’ maneuver to relieve Ladysmith by crossing the Tugela, Roberts would relieve Ladysmith by crossing the Modder. Sir John French (the last man out of Ladysmith the previous spring) led the British cavalry in a daring raid right around Boer lines at Magersfontein and shattered the ring around Kimberly.* Soon the entire western Boer army was in full flight back towards the Free State – but Roberts was hard on their heels and soon to surround and bag (nearly) the lot. (That was a significant nearly, for the record).

Over on the Tugela, Buller had tried once more to get across at Vaalkraanz the week after Spion Kop, with much the same results as before – the British had a sound plan executed terminally slowly, and Botha was able to shift his little force to cover it. The only reason Vaalkraanz never achieved the notoriety of Colenso or Spion Kop is that Buller realized he was about to stick his hand in the bear trap again and yanked it out before it could snap shut, ending the operation prematurely perhaps but at a low cost in casualties, for which his men were grateful (as pilloried as he was about to be in the press and by the British government, his soldiers adored General Buller). As word of Roberts’ victories spread among the commandos on the Tugela, many demoralized burghers upped stakes and lit out for the Drakensberg passes, to defend their homes from the invaders or just giving up the war as a bad job (fair enough).

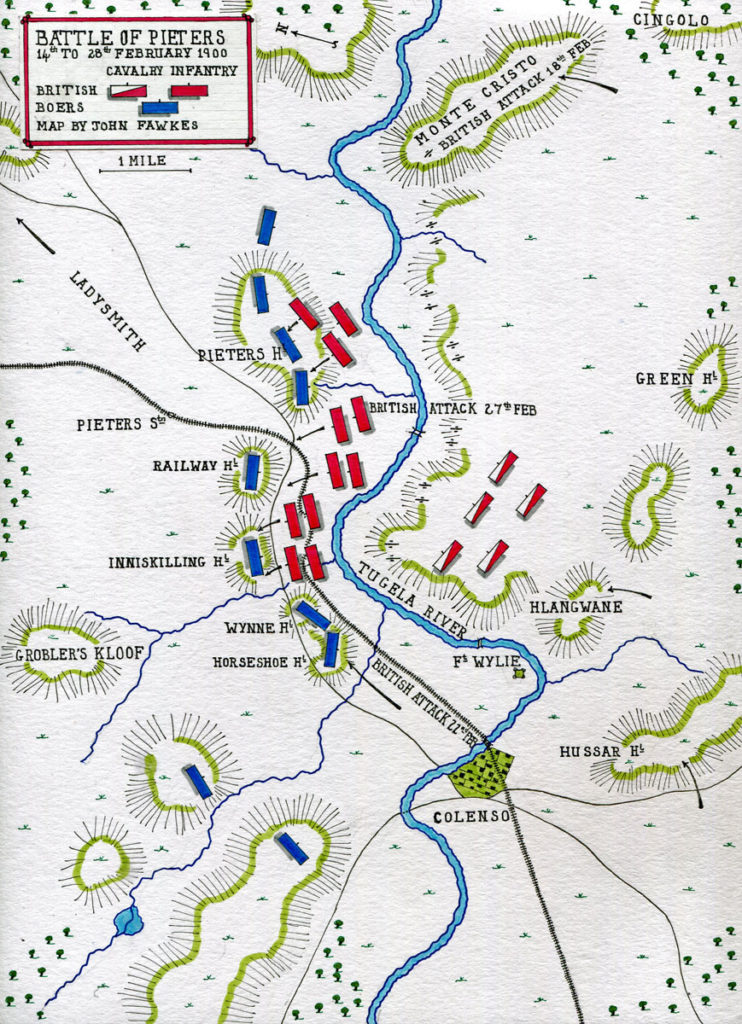

A month after Spion Kop, in late February, Buller at last succeeded in his original objective in Natal. In a series of actions beginning at Hlangwane (that isolated hilltop at Colenso that was the key to the entire position), Buller remarkably and alone among the British generals hit up on the winning tactics for the war. First, he finally started acting like a general instead of a disinterested observer: In the February battles all of Buller’s army would operate in concert, instead of as isolated brigades as hitherto. Second, he used combined arms at last: a steady, deliberate advance, hill to hill, each advance heavily supported by shellfire from the artillery. The next hill taken, the artillery would be brought up and dug in, and the Boers blasted off the next hill, and then the next, and then the next…after a few days, eventually the Boers ran out of hills (and admittedly the patience for being repeatedly blasted off them) and soon enough Botha’s entire army was disintegrating. Bullers’ relieving columns rode into Ladysmith on the last day of February, 1900 – a day after the entire western Boer army had surrendered to Roberts. By the middle of March Bloemfontein had fallen, and by June so, too, had Pretoria. By September the last organized Boer armies had been driven from the field.

But the war didn’t end there. Their capital occupied, their armies dispersed – the British confidently expected the Boers to surrender as soon as they realized they were beaten. Only…no one had gotten the Boers the memo that the war was over. Through the spring and summer of 1900, and then through the winter, spring, and summer of 1901 into 1902 the war dragged on, as isolated bands of Boers, well-mounted, fast moving, intimately familiar with the terrain, and lionized by the populace (seriously, De La Rey, the man who won the battle of Magersfontein in 1899, became a folk hero), raided isolated British garrisons and tore up the railroad all throughout the occupied Transvaal and Orange Free State. In response, the British scorched the earth – Boer farms and eventually entire villages were put to the torch, lines of barbed wire stretched like spider’s webs across the country, parceling it into smaller and smaller pieces, a massive system of blockhouses to defend the railroad gradually spread from the Cape clear to Pretoria, and, most infamously of all, the Boers’ wives and children were herded into concentration camps to isolate them from their men still fighting in the field. Something like 25,000 women and children, over 5% of the Boer population, died in the camps – herded there by the invaders their husbands were desperately fighting to eject. In the end, Britain deployed over half a million soldiers to the little republics (which had a combined Boer population of only about 450,000), mercilessly stamping out all resistance to imperial rule. By May, 1902, their homes burnt, their families dying, the last Bittereinders threw in the towel. Transvaal and the OFS ceased to exist as independent states and became part of the united British South Africa.

The war cost the empire billions of pounds (more than any previous war in their history) and tens of thousands of lives – over 22,000 of the 500,000 khakis died in South Africa, about ⅔ due to disease. The commandos lost about 6,000 men in combat, but a further 50,000 South African civilians died in the vicious guerrilla war that followed – about half of them Boer, half native Africans. It was by far the bloodiest and most destructive war ever fought south of the Zambezi.

A burgher leaving his wife and child to join the commandos. Statue at the Anglo-Boer War Museum in Bloemfontein, November 2021

So in the end, Spion Kop was a lot of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Yes, the sacrifice of so many burghers’ lives delayed the relief of Ladysmith a few weeks – but the Boers lost the war anyway. Yes, Thorneycroft’s desperate stand on that shell-torn hilltop had won the British a chance to break through to the besieged town – but the British didn’t realize what they had and threw the gains away. In the end, nothing much would have changed had the two sides simply glared at each other all through January and February, 1900, save that a lot more men would have been alive at the end of the business. But, regrettably, that’s not how war works.

*He also rode most of his horses to death in doing so, pretty much entirely unnecessarily. Roberts was much more wasteful of human and animal life than Buller was.

VII. Consequences

Oil painting of Spion Kop, 1902, displayed at the Anglo-Boer War Museum in Bloemfontein

So, what happened at Spion Kop?

To my mind, more than anything else it illustrates how chaotic and confusing battles are. No one had any clear picture of what was going on. The men at the front – Deneys Reitz, Thorneycroft, Woodgate – had a vision of hell atop the mountain, and knew perhaps which patch of ground they held, but had no clue what was going on on the hilltops around or on the lower ground. The commanders – Warren, Buller, Botha, Coke, Schalk Burger – had no better idea, with repeated orders and counter-orders shelling the wrong hill, or stopping the shelling of the right hill, or sending the men up the wrong slope, or halting them too early. Reliant on word-of-mouth messengers who had an inconsiderate tendency to get lost or get themselves killed before delivering their message, the commanders got a confused and out-of-order view of the fighting.

The Boer system of warfare showed its limitations – resolute and stubborn in fixed positional defense, the Boers were not able to effectively respond to a British night attack on a crucial position (one that was too lightly defended, to boot) – the only assaults were made by volunteers, and those attacks were ineffective. Towards the end of the battle many commandos’ morale broke entirely and the army teetered on the brink of disintegration.

However, the Boers were saved by British incompetence, mostly on the part of Warren. Thorneycroft was a mere colonel left to fight the battle alone all day – with no orders or moral support other than a single infusion of reinforcements. Someone else should have relieved him at the peak soon after sunset, Warren should have visited himself to get a personal view of the situation, the entire half of Warren’s force that sat idle all day should have pressured the Boers (who came very near to cracking up as it was). Instead, Warren sat on his ass in his headquarters, most of the other commanders washed their hands of responsibility, and Thorneycroft’s nerves broke under the strain.

Ultimate blame must lie with Buller. Buller was repeatedly let down by his subordinates. Symons and White ignored his recommendations for the defense of Natal and unhinged his entire strategy (the same strategy that Roberts ultimately employed successfully). Similarly, his strategies at Colenso and Potgieter’s Drift were sound enough, but blunders by Hart, Long, and Warren doomed the imperial efforts. But a general is not excused by his subordinates’ failures! Buller’s job was to ensure he put men in position to succeed – Long and Hart should have been more closely supervised, and Warren never trusted with an independent command after he blundered the opening of the campaign so badly. Buller’s excuse was he didn’t want the men to lose faith in Warren, but surely an outright defeat is worse than the men seeing one incompetent replaced? Buller is the man who placed those officers in positions to sabotage his efforts, and so ultimately Buller is responsible for the British failures along the Tugela and the mad bloodletting at Spion Kop.

Other lessons emerge – the importance of scouting, the crucial role of staff work and rapidity of execution, the nerve to hang on even when you think you are on your absolute last reserve of strength – it’s the little details that made the difference at Spion Kop, not grand failures of strategy or tactics. Any idiot can work out strategy. Logistics and organization takes talent.

—-

Monument to the tens of thousands of dead Boer civilians, Bloemfontein

Ultimately, the Boers lost their war and their freedom – but what they could not defend with the Mauser, they regained at the ballot box.

Eight years after the war, Transvaal, the Orange Free State, Natal, and the Cape were formally joined in the Union of South Africa – no longer 4 independent, jostling colonies, but one unitary state. The cherished dream of Bartle Frere came true at last, nearly 50 years after it was but a gleam in his eye. To soothe ruffled feathers, every colony got a piece of the pie: the President was housed in the old Transvaal presidential manor in Pretoria, the legislature met in Cape Town, the OFS capital of Bloemfontein became home to the judiciary, and Natal’s garden capital of Pietermaritzberg played host to the official government archives (Bloem and Pietermaritz also received monetary compensation as a consolation prize). The Afrikaaners quickly dominated the new dominion electorally, and would in fifty years eventually secede from the empire altogether, setting their new Republic of South Africa up as a Boer ethnostate, keeping the non-Boers in line through one of the most thorough and repressive racial regimes in the modern world – apartheid.

Following the war, the British army took home a number of lessons. After careful, exhaustive examination of the battle of Spion Kop, the army did the eminently sensible thing and officially blamed the entire fiasco on the most junior officer involved, Thorneycroft. More reasonably, they took the lessons in Boer marksmanship to heart, and twelve years after the war, the BEF marched into Belgium as the best-shooting infantry on the continent.

The man at their head, Sir John French, won his spurs in the Boer War – escaping from Ladysmith and leading the cavalry with talent and distinction all through the fighting. One of Sir John’s subordinates, Major Douglas Haig, who led a battalion through many of the later guerrilla fights, would also rise high.

Sir George White, the man who allowed himself to be penned up in Ladysmith and so scuppered Buller’s entire warplan, was broken by the siege. He left South Africa soon after relief for health reasons, then quietly retired from the army and became governor of the Royal Hospital in Chelsea after the war, dying in 1912.

Marshal Joubert, the Boer who penned him in, did not live to see the end of the war. Joubert never recovered from the fall from his horse in December 1899 and died early in 1900.

William Gatacre, who started Black Week by blundering his command at Stormberg, never recovered his reputation. He left the army in 1904 and went exploring in Ethiopia, where he died of fever in 1906.

Lord Methuen, who came to grief at Magersfontein and so precipitated Buller’s disastrous attack at Colenso, served courageously if not especially intelligently through the war, even being captured in a guerrilla attack late in the war (his chivalrous opponent released him due to the wounds he suffered, and Methuen became a lifelong friend of the Boers). He eventually rose to field marshal, organizing the BEF in early 1914 and serving as governor of Malta.

His opponent at Magersfontein, De La Rey, became one of the most celebrated and successful guerrillas, living on in song even to this day. He died in 1914 in a police skirmish, preparing to rally his people against the British and for the Germans.

Many of the participants at Spion Kop did well in life. Louis Botha, the Boer commander, was promoted to Commander-in-Chief after Joubert’s death. He rose high in South African politics after the war and became the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa. He loyally brought the dominion in against the Germans in 1914 (suppressing a Boer revolt in the process) and was vocally pro-British. He died of Spanish influenza in 1919.

Deneys Reitz, the young burgher, fled the country into exile in Madagascar after the war. While there, he composed his book Commando: A Boer Journal of the Boer War and nearly died of malaria. Returning home around the time of the Union, he became a lawyer and politician, rising as high as deputy prime minister in the new dominion.

The stretcher-bearer, Mohandas Gandhi, led his Indian volunteer ambulance corps through the war and then returned home to Durban. He became an intellectual leader in the small Indian community there and agitated for equal political and social rights for Indians in South Africa, as the British began to sacrifice colored and black rights in order to better integrate the conquered Afrikaaners. Later, he took the lessons he learned from the struggle there and returned to his homeland in India, where he became modestly prominent in that dominion’s struggle for independence.

The young messenger and war correspondent, Winston Churchill, found the entire war thrilling. He published a book on his experiences, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, which was a best-seller (no wonder, it’s a real banger), but decided the life of a journalist wasn’t for him. He eventually went into politics, where he had some little success.

Thorneycroft received the only public blame for Spion Kop while behind closed doors the War Office squabbled over the catastrophic failures of its high command staff. However, he was also a hero of the battle and so served ably throughout the war. His career stalled after that, though, and he retired from the service in 1912, living quietly until 1931.

President Kruger fled the country of his birth in the fall of 1900, as British armies closed in on Pretoria. He never returned to the Transvaal, dying in exile in Europe – a sympathetic, but also faintly embarrassing character for most of the monarchs there.

Redvers Buller had accurately predicted the Boer strength at the start of the war and warned his subordinates not to get trapped on the wrong side of the Tugela, and was ignored, upsetting his entire plan of invading Transvaal and the OFS via the Bloemfontein railway instead of the difficult Natal mountains (Roberts naturally adopted this as his own plan when he took over, leaving Buller…stuck in the Natal mountains). He had also warned of Boer fighting qualities, and accurately predicted that the occupation of Pretoria would not end the war, predicting a long guerrilla struggle – but was again let down time and again by Hart, by Long, by Warren. His men loved him, but on his return to England Buller was made the scapegoat for the entire fiasco of the imperial war effort in South Africa (with lots of British army politics playing into it, Indians vs. Africans, etc, etc) and was drummed out of the service. He was philosophical about it, telling his wife, “It’ll be all the same in hundred years.” He died in 1908.

—-

The Drakensburg, viewed from just south of Spion Kop, November 2021

Given that Spion Kop was ultimately a nothing battle over a nothing hill, why is it still so well-remembered, in ways that Colenso, Magersfontein, Talana Hill, and others are not? To be sure, hardly anyone could give you any details of the battle, not even who was fighting. But the name Spion Kop resounds. Why this cultural presence for a battle that lacks all real significance?

A few reasons, I think. Partially it’s the star-studded cast – Botha became prominent in South Africa and abroad for his politics after the war, and helped popularize the battle. Gandhi, of course, was there – the only time he saw shots fired in anger, I believe. And most famously, Winston Churchill, who would make reference to the battle to the end of his life, the closest he got to the front in any of the three major British wars he found himself involved in. Churchill helped cement the words “Spion Kop” in public consciousness.

A second reason is – Liverpool. Woodgate’s Lancashire Brigade bore the brunt of the fighting for the kop. When the Lancashires went home, soccer was starting to really explode in popularity all over England, and stadiums were excavating great mounds of dirt to house all their new spectators. The returning veterans likened these earthen mounds to the ubiquitous South African hills they had fought and bled over – so they nicknamed them “kops.” And at Liverpool was the most famous of all kops – Spion Kop. To this day, the name is immortalized amongst the fans, even celebrated in songs like Poor Scouser Tommy. You might have heard it yourself, if you watched the recent Premier League final (alas, poor Liverpool).

The war itself is little remembered outside the old Dutch republics. Most famous are the British concentration camps, usually brought up to contrast the later Nazi extermination camps. Spion Kop is marked with just a little sign, and there’s almost nothing at all in Colenso or Ladysmith (at least that I saw).

The Anglo-Boer War Museum in the City of Flowers, Bloemfontein, is a neat little modern building set amidst a beautiful park. Inside are massive wall-sized paintings of the great battles – Ladysmith, Colenso, Spion Kop, Paardeburg – and the table and chairs from the failed Bloemfontein Conference are present, as well as room after room displaying artifacts and exhibits depicting life on commando, life in the concentration camps, medical care, the impact of the war on Africans, and so on. It is a well-done museum and I enjoyed my time there, but it is very pro-Boer and regrettably taking pictures inside was not allowed.

The Boer “Wall”, the name of every man who was KIA on commando during the war.

Outside is a massive monument to the dead in the concentration camps, and statues honoring commando heroes dot the grounds. Most significant is a long, winding wall, similar to the Wall in Washington, listing the name of every single man who died while on commando serving the republics. It is a peaceful, somber place on the whole.

And the much, much longer wall commemorating the civilians who died after being imprisoned in the British concentration camps.

And the Kop itself sits quietly there, behind the Tugela still. The modern road from Durban to Joburg (which is still the city of gold, a hundred years later) runs along its base, most of the motorists little knowing about the brutal struggle that raged on its top one summer morning over a century ago.

The peak is small – just a small half-acre of ground that Briton and Boer fought for. The trench that Woodgate’s men scratched out of the rocky ground that misty morning is still there. Filled in now, though. The Boers used it as a grave for the hundreds of dead on the hill, and it is their grave to this day. A little stone cross marks the resting place.

The view from the top is spectacular.