Part VI: The Battle of Spion Kop

Quote

The Grand Old Duke of York

He had ten thousand men

He marched them up to the top of the hill

And he marched them down again

It is said that, back in 1835, when the Boers had at last successfully negotiated the steep and anguished passes of the Drakensberg, wrestling their oxen and their wagons through the precipitous slopes, they first came to the top of a hill. From here looked out at the green, rolling hills of Natal and knew that they had come to a new Canaan – green and good, flowing with streams and covered in flowers and fruit trees. It was truly a promised land given to them by God as his chosen people. The hill they paused on to view their new home they called forever after Spion Kop.

Sunset in Natal near Spion Kop. The first trekBoers would have seen something like this from the hilltop.

Buller’s march to the hill of destiny began on January 9, but driving Natal midsummer rains turned the ground to a sea of mud and it took until the 15th for the British army to straggle into Springfield (today called Winterton), twenty miles west of the main road to Ladysmith. Buller himself at last rode forward to the top of Mount Alice to survey his proposed crossing site. What he saw was, well, pretty discouraging – all around Potgeiter’s Drift stood more of those wretched kojpes, creating a sort of amphitheater around the northern side of the drift defined by the Rangeworthy Hills. Any advance over Potgeiter’s would be an invitation to another slaughter, and Buller was nothing if not careful with the lives of his men.

Reminder image of the situation in early January – the siege of Ladysmith, the Boer lines on the Tugela at Colenso, and Buller’s army lying at Frere.

Buller’s three possible options. In yellow, a frontal assault up the railroad at Colenso – tried and failed. In blue, a flank march on the right – through tangled hills and ravines and a long march to Ladysmith on the far side, and no possibility of cutting the Boers off from the Drakensburg passes to the west. Finally, in green – a march on the left through Potgeiter’s Drift, over a comparatively low line of hills, and then open ground to the town. It’s not hard to understand Buller’s choice.

So the general improvised. His maps showed a second drift, five miles further up the river, called Trickhardt’s Drift. Of his five brigades of infantry, he had left one back at the camp at Chievely to cover the railway to Durban. He would use two others, Lyttleton’s and Coke’s, to make a demonstration attack at Potgieter’s, while he sent the bulk of his troops – Hart’s and Woodgate’s brigade, togther with the cavalry comprising Warren’s division – to cross at Trickhardt’s and catch the Boers in the flank (a plan more or less identical to the plan at Colenso and, well, every other British battle in the Boer War).

Warren was ordered to move out on the 16th, cross the Tugela at Trickhardt’s, and then swing west of the hill of Spion Kop and get into the open country beyond the Boer right flank, whence he would roll the Afrikaaners up, clear Potgeiter’s Drift, and open the way to Ladysmith. Warren was unenthusiastic about the assignment – there was no chance of surprise, as the slow British march had allowed Botha plenty of time to reposition his commandos and dig fresh trenches across the Rangeworthy Hills, and Warren wasn’t convinced that the Boer right didn’t extend beyond Spion Kop. He dragged his feet – it was not until sunset on the 18th, three full days, before Warren’s entire force, now reinforced to three brigades, had marched the five miles to Trickhardt’s and crossed to the north bank of the Tugela. Dundonald’s cavalry, who had been engaged at Hlangwane at Colenso, ranged out to the northwest and actually found the Boer right unoccupied – but Warren recalled him, rebuking him that the purpose of the operation was a junction with Buller’s forces at Potgeiter’s and the relief of Ladysmith. He was ordered to refrain from further efforts to turn the enemy right.

Warren spent days on the low river plain just beyond the Tugela, slowly establishing batteries and thoroughly shelling the range of hills just to the north, arguing with Buller that this was, of course, entirely necessary so he could advance with minimum loss of life. Meanwhile, Botha continued to rush his commandos into position, and the Boer line gradually extended from the Rangeworthy Hills, across Spion Kop in the center, and on to Bastion Hill in the west, which became the Boer right. It was not until January 23, a full week after Buller ordered him to turn the Boer right flank, that Warren began to move off the floodplain and ordered his men up into the hills.

Spion Kop viewed from the south, near where Warren’s headquarters were (some distance off the road to the left).

Spion Kop was the highest eminence in the Boer line, sitting about in the right-center. To the east of the hill are a pair of peaks, known as the Twin Peaks, which are joined by a ridge to the kop itself, with a little knoll in between. On the northern side of the kop another ridge runs out, ending in a conical hill. The sides of the hill are steep and difficult to climb, and the Boers had posted no artillery there – in fact, telescopic reconnaissance by the senior officers seemed to reveal just a handful of burghers garrisoning the kop. Buller, frustrated at Warren’s delays and still anxious over the fate of Ladysmith, ordered his subordinate to get his ass moving and to take that hill. Warren, for his part, judged that the hill was vulnerable to a coup de main at night, and that, the kop taken, he would be able to pry the Boers out of the rest of the Rangeworthy Hills.

He arranged his men into two groups. The left was under the direction of General Clery and was to move against Bastion Hill. The right was under General Coke and would move on Spion Kop. Coke in turn delegated the task of seizing the hill to General Woodgate’s brigade, which included Colonel Alexander Thorneycroft’s regiment of mounted infantry. Buller contented himself with the role of the chorus in a Greek tragedy – taking a general interest in the action, yet not personally concerned in it. The confused command arrangements were to have serious consequences for the imperial war effort.

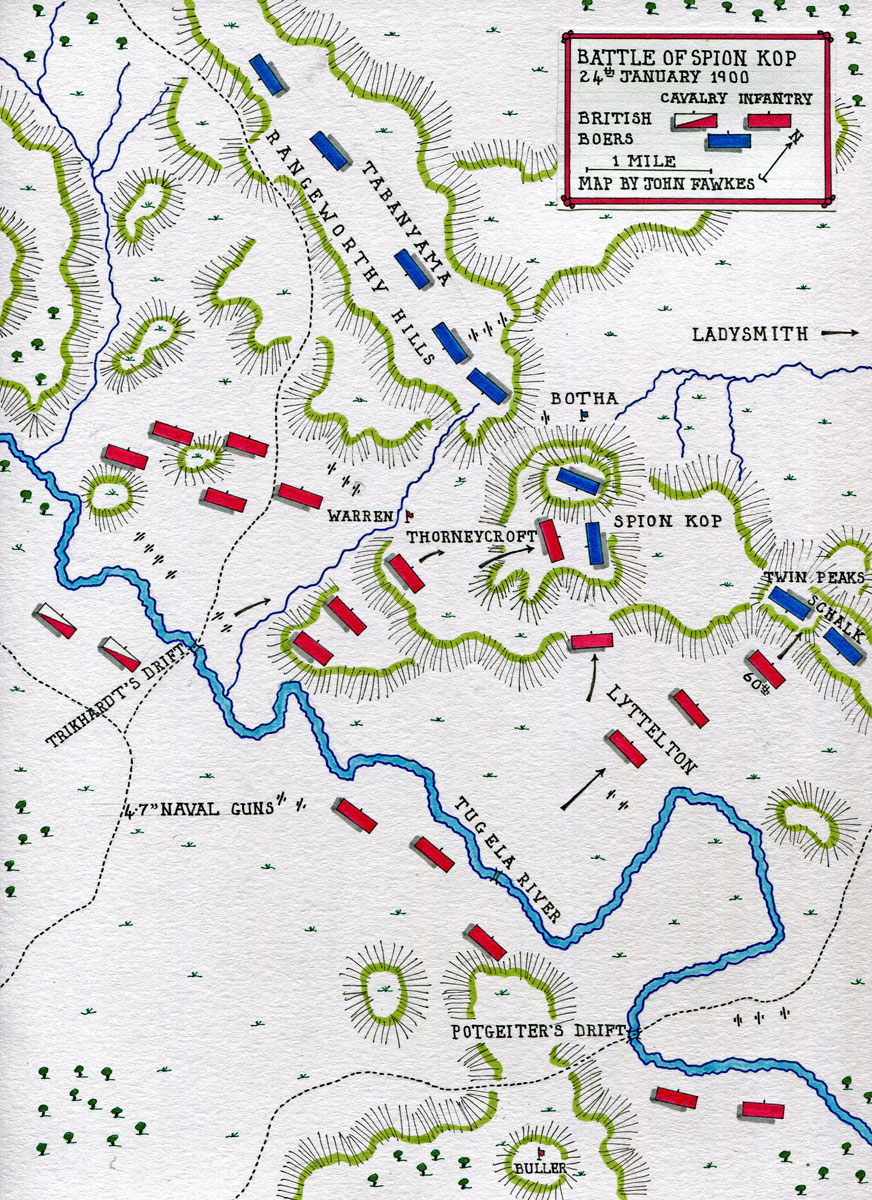

Overview map of the battle.

Thorneycroft, a large, barrel-chested, red-faced model of a British officer, led his regiment at the head of the column in the pre-dawn darkness on January 23, 1900. He had recruited most of his men – Natal colonials and Transvaal uitlanders – himself and the mounted infantry had done excellent scouting and patrol service in the campaign thus far. Now they had the place of honor at the head of the attack on Spion Kop. The khakis crept slowly through the night, scrambling over rocks, climbing at times on hands and knees, and keeping as dead silent as they could. Dawn was near – but thick mist hung over the summit still. Suddenly, a startled voice cut through the darkness – “Werda!?”

Thorneycroft bellowed the signal to attack: “Waterloo!” The khakis immediately flung themselves to the ground, as above them a ragged volley of Mauser fire spat out into the predawn. Then the British picked themselves up and hurled the line forward in a bayonet charge, yelling, “Majuba! Majuba!” Fired by the memory of that humiliation eighteen years before, the mounted infantry swept over the crest in a wave – and the Boer picket, less than seventy men in all, took to their heels and fled. Spion Kop, and with it the key to Ladysmith, belonged to the British army.

Now, the mist in the Natal midlands is the thickest I have ever seen in my life. At times it is so thick that one can’t make out, for example, a highway bridge even when you’re standing on the exit. Buildings and landmarks less than a hundred yards away vanish utterly. Such was the mist on the summit of Spion Kop that morning. Woodgate, relaxed, traced out a trench line and a few sapper started scratching out a fortification from the rocky ground, while their brigadier penciled a message to send back to Warren:

Quote

“Dear Sir Charles –

We got up about four o’clock and rushed the position. We have entrenched…and are, I hope, secure; but the fog is too thick to see. Thorneycroft’s men attacked in fine style. I had a noise made later to let you know that we had got in.”

Had the mist lifted, the British would have been able to see clear across the high plain to a distant cluster of trees and tin-roofed houses – Ladysmith was nearly theirs.

View northeast towards Ladysmith

—-

The burghers fleeing Spion Kop raced down the northern slope into the mist. A mile and a half to the north of the summit, they came upon a little tent, with a small, bearded man sitting outside smoking his morning pipe: Louis Botha himself. Spion Kop was lost, he was informed, and the Boer position breached. He nodded gravely, unperturbed, seemingly, and commented that the burghers would just have to take it back.

Now, Botha had perhaps 4,000 men defending the river line from the Rangeworthy Hills in the east to Bastion Hill in the west, holding back at least three times their number in imperials. However, the key to his position was that he had several heavy guns and excellent positions on the reverse of the ridgeline to use them from. The Boer guns, sheltered from the much-superior in number British artillery, could play freely on the summit of Spion Kop and give cover to his infantry. Botha sent orderlies galloping up and down the line, pleading for volunteers to storm the summit and directing the fire of the Long Toms on Woodgate’s thousand men. In all, Botha was able to round up about a thousand burghers – fully a quarter of his force – to bravely attempt the task of recapturing Spion Kop. Henrik Prinsloo, commandant of the Carolina Commando, exhorted his men: “Burghers, we’re now going to attack the enemy and we shan’t all be coming back. Do your duty and trust in the Lord.” News of Spion Kop’s fall had flashed up the telegraph wires all the way to Pretoria, and President Kruger himself was on the line pleading with his citizens to be brave and to regain the kopje. If the Afrikaaners moved quickly enough, though, they could seize superior positions to the khakis and lever them off the summit with better firepower and Boer craftiness. The situation was accordingly dangerous but not yet desperate.

Among the burghers moving up towards the crest was a young man named Deneys Rietz. His father was former President of the Free State and the serving Secretary of State for Transvaal, but among the egalitarian Boers his son was just another infantryman. Reitz had invaded Natal with his commando, and returned to Pretoria amidst the calm of mid-January – but only a day later his father placed him on the next train to Ladysmith, as Buller’s attack was hourly expected. Reitz had arrived two days before and watched Warren’s furious shelling of the Rangeworthy Hills, seeing his fellow citizens cut to pieces by the attacking imperial artillery (including a father and a son from the Frankfort Commando killed by the same shell). The Boers were hopelessly outnumbered by Warren’s massive force and short of ammunition, and daily expected him to make his move up into the hills. Instead, he had crabbed sideways, into the center of hte position at Spion Kop.

Woken in the night by the sound of gunfire from the peak, Reitz spent his morning sheltering behind a wagon from the British shellfire, until one of Botha’s orderlies galloped up: Spion Kop must be retaken. Reitz and his comrades grabbed handfuls of Mauser ammunition from the wagon and galloped off, leaving their horses at the foot of the hill. Above him, he saw Prinsloo’s Carolina Commando leading the way, dusty dun-clad figures with slouch hats and fierce beards clambering up, falling down as khaki men in pith helmets leaped up from behind rocks and trees higher up the slope and opened fire. Then the Boers were on the British line, there was a moment of struggle, and the fighting passed over the crest and onto the plateau beyond, out of Reitz’s sight.

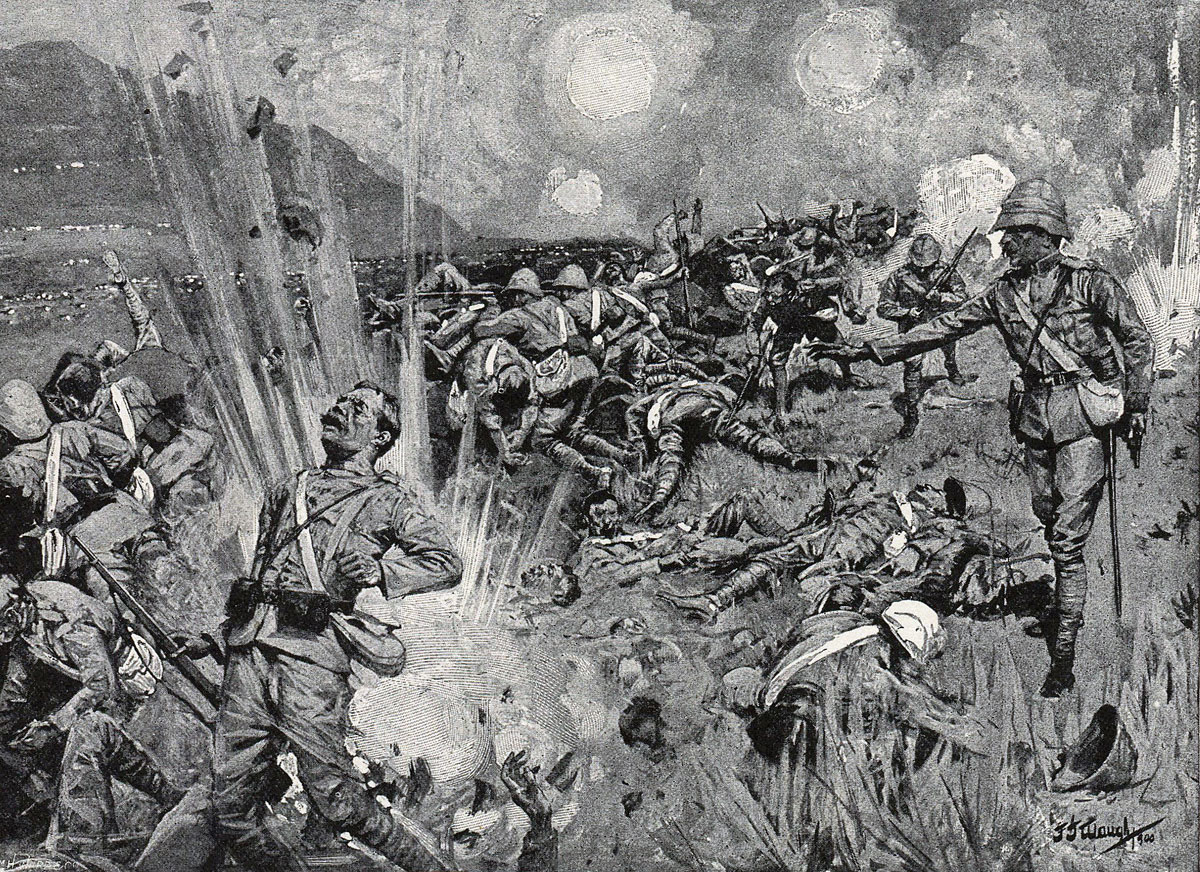

The Boer assault on the British trench at Spion Kop

Reitz scrambled up after the Carolinans, seeing men he had drank coffee with just an hour before falling dead or wounded, worming his way onto the crest. The enemy could not be seen, but the showers of earth from bursting artillery, British and Boer, fell on all sides. He huddled behind a rock, squeezing off a round downrange every now and then, and tried his best to stay alive.

——

The situation was desperate on the other side of the hill. Most of Woodgate’s brigade had thrown themselves down on the ground and slept after Spion Kop was taken, while a few sappers dug a trench along the top of the hill. Woodgate was casual, as his message to Warren showed, and once the mist lifted he would survey the position, get some artillery up the hill, and then proceed to blast the Boers out of their defensive line. What he saw when the mist lifted, though, horrified him:

The British had fortified the wrong damn spot.

The sappers, working in the pea-soup fog, had fortified what they thought was the crest of the hill – only to find out that they didn’t hold the entire peak, only part of it. The slope ran away to the north a few dozen yards, perhaps an acre, before dropping down towards the plains of Ladysmith. Off to his right was a little knoll, ahead of his left-center was the conical kopje. None of these features had been present on the agricultural survey map the British were working from. None of them had been visible from their telescopic reconnaissance in the days before. All of them commanded his own little slit trench – and all of them were swarming with Boers.

Sketch plan of the peak. The British trench is on the geographic crest, but not the military crest – men in the trench can’t shoot down the slopes of the hill in front of them, letting the Boers approach to the very edge of the hilltop. The little knoll is also visible as a distinct peak in the photo of Spion Kop above.

Woodgate ordered his men forward to the crest line, where their rifles could at least check the Afrikaaner counterattack that even then was speeding towards him. The khakis tried to dig in on the crest – the military crest, not the geographic crest – but already the summer sun was rising and the storm burst.

Dutch cannon winked and flashed on the hills all around Woodgate, and shells began exploding amidst the British. The cannon fire soon drove them back as enemy infantry swarmed up the hill, and soon enemy riflemen opened up from the little knoll on the right and the conical kopje ahead, both of which enfiladed the little British trench. Woodgate soon fell, mortally wounded by one of Botha’s guns, a Boer commando threw the British back from the military crest (Prinsloo’s Carolinans), and the British were soon clinging to the trench, barely an acre of ground, by their fingernails. The ground was stony and broken, and the imperials had only managed to dig about a foot and half deep – even crouched their heads and shoulders were exposed to enemy fire, and all that hot January morning enemy fire flailed at Woodgate’s little force.

Under fire at Spion Kop

With the death of the general, command devolved upon the senior colonel present, Malby Crofton, CO of the Royal Lancasters. All was confusion. Nearly a thousand men were packed onto the hilltop, and there was not cover enough for those massed ranks. Rifle and shellfire mutilated and massacred men by the dozens, Crofton did not know the position, where his men were, where the Boers were – chaos. He knew that he needed reinforcements, fast, but he felt he had not time to write a report for Warren, and contented himself with ordering a nearby officer to signal SOS via flag relay. Crofton then retired from the scene.

Thorneycroft, colonel of the Natal mounted infantry who had led the attack, was everywhere that morning. He roamed all through that murderous acre, rallying the scattering British, leading counterattacks on the Boer-held crestline, being driven back into the British trench, and organizing still more counterattacks. Barely twenty yards separated the British trench on the peak of the hill with the Boers crouched on the edge of the northern rim of the peak, and it was rapidly filling with wounded and dying men as the two white races of South Africa brawled for the summit.

———-

Three miles away, at his headquarters on Three Tree Hill, Warren received the message from Woodgate at about 9:30 am:

Quote

“Dear Sir Charles –

We got up about four o’clock and rushed the position. We have entrenched…and are, I hope, secure; but the fog is too thick to see. Thorneycroft’s men attacked in fine style. I had a noise made later to let you know that we had got in.”

So all seemed well. But for the last hour he had heard roaring gunfire from Spion Kop, and couldn’t make out what was happening. Then, hard on the heels of Woodgate’s message, came one from Crofton: “Reinforce at once or all is lost. General dead.” Warren was caught off-guard by the speed and ferocity of Botha’s counterattack, and replied to Crofton that he was sending reinforcements. He ordered General Coke to take his brigade to the top of that damn hill and figure out what the devil was going on. He also asked Lyttleton, over towards Potgeiter’s Drift to the east, to give assistance, saying “This side is clear.” Apparently Warren thought that he was still astride the Boer right and that the attack on Spion Kop was coming from the direction of Potgeiter’s. He also thought that Woodgate had taken the Twin Peaks, as well, as he ordered Lyttleton’s artillery to cease shelling the Boer position on those hills for fear of friendly fire. Bottom line: Warren didn’t have a fucking clue what was going on, and he took zero positive steps during the day to rectify that, preferring to stay snug in his headquarters and hurl out some artillery shells to look busy instead.

A few miles away, atop Mount Alice, Buller and his staff peered anxiously through their telescopes at the storm of fire atop Spion Kop. Buller was cursing Warren. He already felt that Hart and Long had cost him the battle of Colenso through their impetuosity – now Warren was blundering away his second attempt on the Tugela through his appalling dilatoriness and passivity. But he refused to take command himself. Such a move, Buller felt, would undermine the confidence of the men in Warren. And so he left the majority of his own army under the command of a man he thought was too dilatory to get the job done. Instead Buller acted the Umpire in a wargame rather than a commanding general in the field, content to observe his subordinates’ solutions to the tactical puzzles presented. The only positive step he made – well, he could see through his telescope the heroic figure of Thorneycroft, rallying the troops, now here, now there, leading the defense. A message was flashed to the heliograph on Spion Kop, where the operators dodged and ducked amid the storm of Mauser fire and high explosive shot: Thorneycroft was to supersede Crofton in command atop the hill.

Colonel General Thorneycroft

—–

The weary, hellish day wore on. Shells arced back and forth from the British positions on the Tugela plain and from the Boer emplacement behind the hills. Reinforcements streamed up the hill, wounded men streamed down it. General Coke sent up his men – the Imperial Light Infantry and the Middlesex regiment, a stream of men in khaki uniforms with gleaming bayonets – and then stopped further reinforcements, since the defense seemed to be maintaining itself and more men on the hill would probably mean more targets. He sent Warren a message to this effect but neglected to inform Thorneycroft. Then, considering his duty done, he took a nap at the base of the hill. Thorneycroft, newly notified of his promotion by a lieutenant who crawled (the first fellow who approached with the message had taken a Mauser bullet to the head) near his position and bellowed, “You are a general!”, hurriedly distributed them along the firing line, stabilizing the ongoing firefight somewhat.

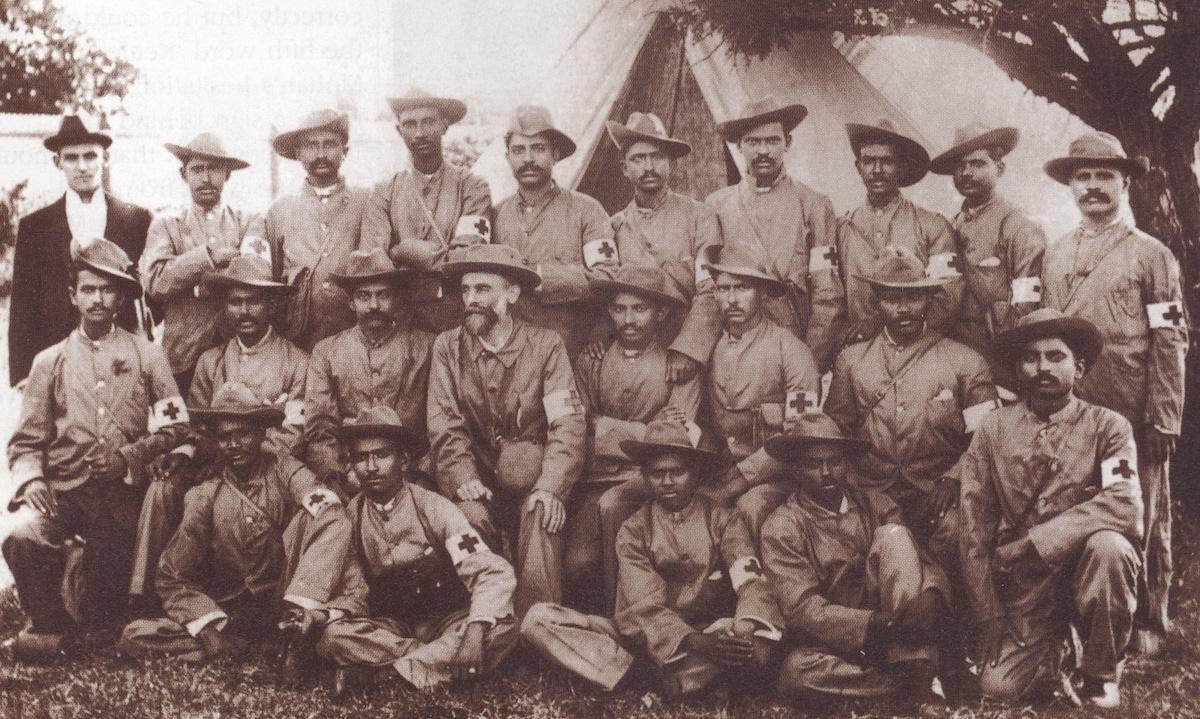

The stretcher bearers caring the men down were, by and large, Natal Indians. That population had been growing rapidly over the last few decades as tens of thousands of indentured servants came from the subcontinent to work the colony’s sugar fields. Wanting to prove their loyalty to the empire, thousands had volunteered to form an ambulance corps. Their leader was a young lawyer, born in Gujarat and trained in London. As one of the only Indian lawyers in South Africa, he was an acknowledged leader of the community. His pacifist ideals forbade him from fighting, but he believed that India’s future lay with the empire. Now, with the help of another man, he carried the stretcher bearing General Woodgate down the steep slopes of Spion Kop, through the storm of artillery fire still being flung about. The two men carefully set the general down near the aid station, peering at their charge – but it was a severe head wound. The general would certainly die. Shaking his head, Mohandas Gandhi wearily started back up the hill to fetch another injured man.

The Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps. Gandhi at center, 5th from left.

At the top, five hours without food and water was wearing the imperial troops down. Most men hadn’t seen a senior officer in hours, huddling in whatever small patches of cover they could find, and most had no clue about Coke’s reinforcements. Some men threw down their rifles and put up their hands, and white handkerchiefs started to flutter on the summit. The Boers, clinging to the crest line just across the bullet-swept summit, tentatively began to venture out. The British, who had begun the battle by shouting “Majuba!”, seemed to be re-enacting that old humiliation.

Thorneycroft, big, angry, red-faced, would have none of it. “I’m the Commandant here, sir!” he said, leaping out of the trench and storming up to the Boer commander on the hill, de Kock.

“Take your men to hell – I allow no surrenders. Go on with your firing.” Bemusedly, the Boers clambered back into their cover at the edge of the hill, while Thorneycroft led his shirkers behind some nearby rocks and began taking potshots at any slouched hats that showed themselves on the crest. Then, he finished distributing Coke’s reinforcing troops around the hill and crawled back to his ‘command post’ in the trench, scribbling out a message for Warren:

Quote

Hung on til last extremity with old force. Some of the Middlesex here now and I hear Dorsets coming up; but force really inadequate to hold such a large perimeter…What reinforcements can you send to hold the hill tonight? We are badly in need of water. There are many killed and wounded. – Alex Thorneycroft.

PS. If you wish to make a certainty of the hill for night, you must send more Infantry and attack enemy’s guns.

The note reached Warren later, but not before first passing through the hands of Coke, who added “I have seen the above and have ordered the Scottish Rifles and King’s Royal Rifles to reinforce…we appear to be holding our own.” This, he said from the safety of the track below the summit, which Warren had no idea of. Then he resumed his nap, and the bemused Warren, receiving both notes, concluded that Thorneycroft was losing his nerve and Spion Kop was fine. He did not give any orders to the great mass of men on his left, crouching below the Rangeworthy Hills under Clery, other than that Clery was “to use his discretion” in opening fire and attacking the Boers to provide a diversion. Clery opted to exercise his discretion to the fullest and did absolutely nothing.

My sketch of the battle of Spion Kop at its height, as accurate as I can make it (ie I traced the preserved British trench line, for example). Warren’s HQ is just below the kop, Botha’s HQ just behind it. To the left Clery sits on his ass and does nothing to attack the thin Boer lines on the Rangeworthy hills, on the right Buller at Potgeiter’s does much the same. In the center Thorneycroft manages a clusterfuck of British troops clinging to the hilltop, commanded by Boers on the nearby peaks. Lyttleton’s attack on the Twin Peaks (more on that below) is developing.

On the other side, Lyttleton, having at last got his men organized around Potgieter’s drift, ignored Buller’s attempts to restrain him and flung his men at the two crests before him – the Twin Peaks, held by the Boers all morning, whence they had been enfilading the brigades on Spion Kop. Lyttleton sent one regiment, the Scottish Rifles, straight up the eastern slope of Spion Kop to join the mess on the summit, while a second, the 60th rifles, went right up the precipitous Twin Peaks.

These slopes had been held that morning by the Carolina Commando and Schalk Burger’s Commando. But the Carolinans had been fighting desperately all day over on the kop and now only General Burger himself held the ridge. He was stretched desperately thin, and the oncoming British – two groups of about 600 men each – seemed unstoppable. The Afrikaaners sighted in and fired, and the bullets tore into the khaki clad soldiers scrambling up the hill, sometimes up slopes so steep they had to crawl on hands and knees. But the British could not be stopped. As the sun sank towards the horizon, at about five pm Lyttleton’s men had gained the Twin Peaks. Schalk Burger, who was a politician back in the Transvaal (and not a particularly successful one), was completely demoralized. He and the men of his commando were soon hightailing it for Ladysmith and the Drakensberg passes beyond – and a massive gap yawned in the Boer line.

By now, the Boer position was disintegrating. The sun was setting and barely two dozen men, among them Deneys Reitz, remained alive on the summit. They now had no choice but to admit defeat, and amidst the gathering darkness the surviving burghers picked their way down the northern slope, scrambling to find their horses and discovering the camp a wreck, as more and more panicked burghers abandoned their commandos and fled for Drakensberg.

In the darkness, Reitz and his comrades saw a lone rider gallop up and shout at them to halt. He didn’t recognize the man, but whispers around him told that it was Botha himself. The Boer general told them to think of the shame of deserting their posts in their nation’s hour of danger. A few men, Reitz among them, heard him and took up defensive positions on the base of the hill. But no one dared return to that deadly summit, where so many of their comrades lay dying.

Botha was nothing if not optimistic, irrepressible and full of energy. Even though he had now lost the main summit of Spion Kop, and had also had another huge hole torn in his right center at the Twin Peaks, he telegraphed Kruger in Pretoria that all was well, and that he would restore the situation. He wrote, too, for Schalk Burger, “Let us struggle and die together. But, brother, let us not give way an inch more to the English.” He promised the frightened politician reinforcements as soon as the moon rose, but Burger himself must plug the hole behind the Twin Peaks. Botha added he knew the English – that they were kopschuw (nervous, skittish) and would abandon the fight, if only the Boers would not give in. But Burger was gone. He and his commando were riding hard for Ladysmith already. As the long night passed and the sky began to brighten with approaching dawn, there was absolutely nothing the Boers could do to keep the British from ripping wide the holes in their lines and driving them clear out of Natal.

But the British high command couldn’t see it. All day the messages coming from Spion Kop had been confused and jumbled. Heliograph operators, dodging shot and shell, garbled their messages, forgot to append signatures, dropped key words. Messengers up and down the kops had been shot or had gotten lost or delayed, wandering the hillsides and the Tugela plain seeking their recipients. Warren, who had not bestired himself from his headquarters southwest of Spion Kop, had no idea what was happening on the summit, but figured the reinforcements he had sent would be enough. Buller, on Mount Alice, could make out the fighting in his telescope but had no idea who was who. He was terrified of another Colenso, though, and of a precipitous attack on the steep hills near Potgieter’s Drift. He ordered Lyttleton to abandon that attack before the idiot got himself into trouble like Hart had.

Lyttleton duly ordered the recall of his men – who had already gained the summit – but the commander of the 60th, Lt. Col. Riddell, suddenly developed a highly selective case of blindness and the brigadier’s orders were mysteriously misplaced three separate times through the early evening. But at last, about seven, Riddell was killed (the missing orders miraculously discovered in his breast pocket), and the 60th at last obeyed orders and withdrew back down onto the Tugela plain.

The trench atop Spion Kop, November 2021.

On Spion Kop the Fog of War hung more densely than ever. Coke, who was lame and unable to move freely about the position, believed that Hill, who had come up with a reinforcement soon after noon, and who was next in seniority to Crofton, was in command on the summit. He thought that Crofton had been wounded, and neither saw Thorneycroft nor knew until the following day that Warren had given him the local rank of Brigadier-General at Buller’s suggestion. Thorneycroft was a junior major in the Army, having the local rank of Lieutenant-Colonel: and with two colonels senior to him present as well as a major-general, he was doubtful as to his status. No instructions reached him from Coke; he was unaware that the Twin Peaks had been taken by one of Lyttelton’s battalions, and he was without means of signalling to Warren. He had no information of the measures which were being taken, such as the dispatch of guns, to make the retention of Spion Kop possible.

Warren himself was criminally negligent – it was only at about 9 pm, even as Reitz’s men were slinking down the northern slopes and Botha was desperately casting about for any brave men willing to plug the gaping holes in his line, that he sent any reinforcements and work parties to the Kop. A party of men with two naval guns was ordered to the summit, with sappers to clear the way. It had been dark for five hours already and no word had been sent to Thorneycroft. Warren left it to Coke to reassure Thorneycroft – but no one had ever mentioned to Coke that Thorneycroft was in charge on the summit! Then, around the same time, Warren recalled Coke to headquarters to consult with him on the business of the day – and Thorneycroft was left alone amidst the dead men in the darkness on the summit.

Hell’s half-acre – the dead piled in the British trench (this photo taken the morning after the battle).

Into this darkness rode at last one final messenger. He picked his way up the hill in the dark, past the torn and mutilated casualties, past the Indian stretcher-bearers and their ghastly cargos, the moans of the wounded, the cries for water from all sides, the stragglers. Atop the summit all was confusion. Only the Dorsets, who had not got into the fighting, were still a unit. 1700 men, from Thorneycroft’s own Mounted Infantry, from Woodgates’ three battalions of Lancashire men, mingled with the two thousand sent to reinforce them – the Middlesex and Imperial Light Infantry from Coke, the 2nd Scottish Rifles sent by Lyttleton all the way to Potgieter’s (or rather, what was left of these units after a day of being lashed at with artillery and rifle fire with no adequate cover). The units had ceased to exist – only small groups of men clustered around their junior officers remained.

The messenger at last found Thorneycroft. He gave him at last a note from Warren – the navy was coming, and so were the sappers. But the colonel was in shock. He had fought for twelve hours, alone, with no orders from higher command, no food, no water, hardly any reinforcements. He had been shot at, blasted with artillery, and had fought hand-to-hand to hold the ground. He had singlehandedly stopped the force surrendering. Now, his broken mind could think of only one thing: retreat. Get the six battalions (more or less) down the hill intact, rather than leave them on the crest to be slaughtered anew in the morning. One of the other colonels, Hill, commander of the Middlesex reinforcements, challenged Thorneycroft’s decision, and questioned why he was in charge anyway, being so junior. No one listened to Hill, though. The messenger, despairing, pleaded with Thorneycroft to remain.

It is worth it to pause to highlight this man. A newspaper correspondent with the Morning Post, the young man had volunteered to join the South African Light Horse as well as a lieutenant. In the advance up from Durban, he had been aboard an armored train that blundered into a Boer ambush. He had escaped, but returned to help the wounded men and been taken prisoner, shipped off with the others to Pretoria. From Pretoria (where he celebrated his 25th birthday in a prisoner of war camp), he had escaped and made his way back to the army on the Tugela, missing the battle of Colenso in the process, but present here, at Spion Kop. He had found the experience of being shot at, in his words, “exhilarating.” Now the young man pleaded with Thorneycroft. But the colonel would not be moved. He turned his back on Winston Churchill and led the rearguard down from the kop.

Lt. and war correspondent Winston Churchill, age 25

After a day of slaughter for its possession, Spion Kop was left in the end for the dead and the dying: 243 British soldiers, four times that number wounded, piled three deep in that little trench they scratched out in the predawn darkness. 335 Boers joined the invaders in death.

As the sun rose, Deneys Reitz and his dispirited comrades, the handful of survivors from the proud Pretoria commando, looked up at the hateful half-acre one last time – and saw a miracle. Two burghers stood atop the kop, shouting with joy and waving their slouch hats for all they were worth. Botha had been right – the British were kopschuw.

Spion Kop belonged to the Boers.