Part II: Historical context

Quote

A war in South Africa would be one of the most serious wars that could possibly be waged. It would in the nature of a Civil War. It would be a long war, a bitter war, and a costly war…It would leave behind it the embers of a strife which I believe generations would hardly be long enough to extinguish…to go to war with President Kruger, to force upon him reforms in the internal affairs of his state, with which we have repudiated all right of interference – that would have been a course of action as immoral as it would have been unwise. – Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain to the House of Commons, May, 1896

The events that led to a bloody tussle for a half-acre of ground atop an obscure hill in the backcountry of southern Africa were set in motion nearly a century before anyone in Liverpool ever heard the name “Spion Kop.” To start at the proper beginning, we need to go back to South Africa’s origins as a violent cauldron of Africans, British, and above all, Boers.

Just who were these Boers? I mentioned them in passing in the leadup to the Zulu War, but now it’s time to examine these jokers in earnest. Boer is simply a Dutch word meaning “farmer,” and the Boers were the farmers of Cape Town. The Dutch East India Company, when it established its trading station in the magnificent harbor beneath Table Mountain there at the Cape, needed to grow food to feed the men and resupply passing ships – which meant importing farmers. These Dutch colonials, the first Afrikaaners, pushed out from Cape Town across the flats and into the encircling mountains that separated the Cape from the rest of Africa. These farmers, rough, doughty, independent, reliant only on themselves and their neighbors for survival amidst a hostile continent, developed a sturdy sense of freedom and independence – one that was threatened above all else by the British Empire. When the redcoats occupied Cape Town in 1804 as part of their death struggle against Napoleonic France, the farmers on the fringes of the colony – the Boers – were outraged. When Britain formally annexed Cape Colony, and, worse, when they outlawed slavery a few decades later, the Boers could tolerate no more. And so the Great Trek was born.

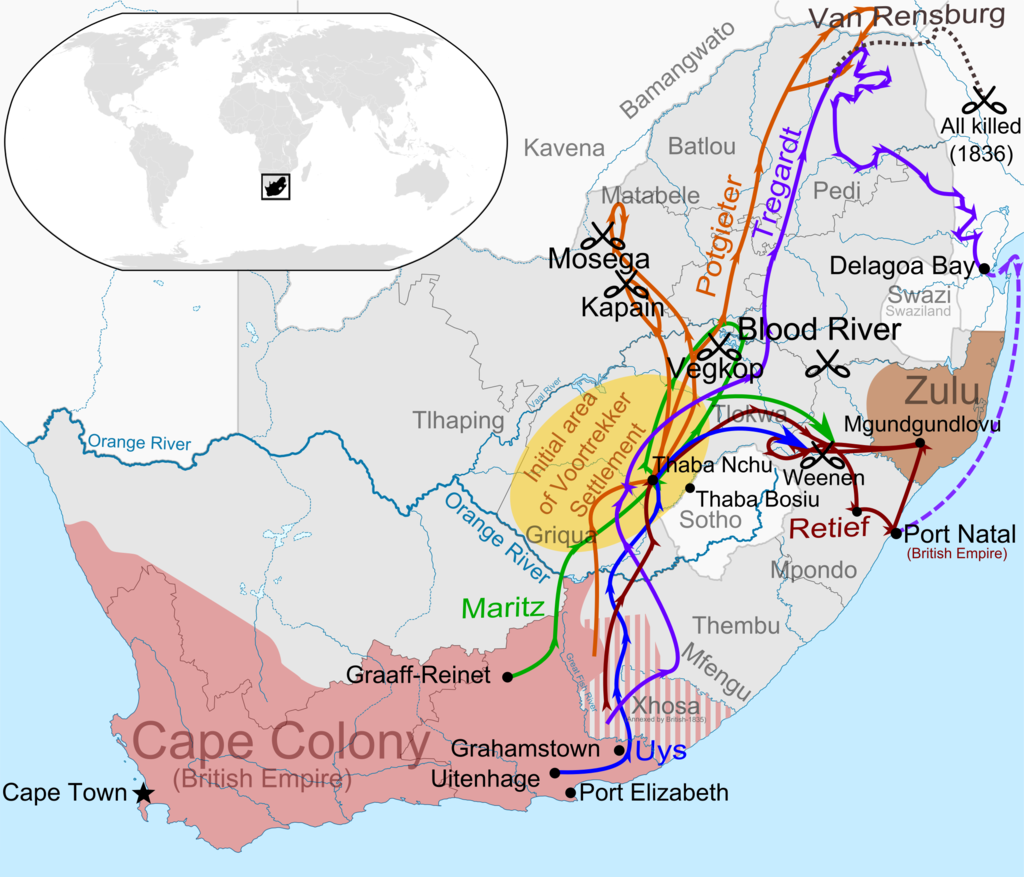

The Great Trek in its magnificent complexity

The Great Trek is the foundational historical epic of the Boers, like the Exodus for the Jews, the Iliad for the Greeks, or the Revolution for the Americans, French, Russians, and others. The Boers loaded up all their belongings onto high-sided wagons, hitched up their oxen and hundreds of livestock, and trekked into the interior of Africa, away from British law and into the wilds. It was a slow process, lasting decades – whenever the arm of the Empire would catch up to them, or if the local neighborhood grew too crowded (say, when another white family settled within a day’s riding distance), the old patriarch of the family would declare that he was trekking, and back onto the wagon everything would go and the farmer with his sons riding alongside, his wife and children in the wagons, would set off once more.

Across the high veldt that sits behind the dividing mountains the Boers trekked, various factions feuding and fighting and fissioning as they went, living alongside or more commonly fighting skirmishes or even full-blown wars with the African tribes they met along the way. Eventually, by the early 1840’s, the Great Trek had settled into three main groups of Boers. One group had trekked clear across Africa and passed through the Drakensberg mountains to descend into a green and fertile country they dubbed Natal. One group had settled early after crossing the Orange River, named for that famous Dutch royal house, and set up a loose confederation of farmers known as the Orange Free State. The feistiest and most independent of all moved as far from the British as they could, across the Vaal river, and set up the Transvaal Republic in the wide lands beyond.

View of Natal near the Drakensberg, November 2021

Natal, situated as it was on the Indian ocean and with the finest deepwater port in east Africa located at Durban, was quickly seized by the British as they expanded eastwards along the coast from Cape Colony, but the two high veldt republics seemed little worth the effort of conquering the recalcitrant Boers and so the British, while declaring their suzerainty over the Afrikaaners, left them largely to run their affairs in peace. The Boers politely pretended that they were a completely free and independent people, and the British politely pretended that the Boers were loyal and zealous subjects. And so the uneasy peace held.

For a while.

South Africa around the time of the Zulu War, 1879

About thirty years after the trekkers had settled down, schemes were brewing in the British-held areas of South Africa. In a nutshell, a coven of high British colonial officers intended to form all of southern Africa into a single united dominion, much as had been done in Canada in the 1860’s. The feat repeated here, in the keystone of the Empire (for South Africa lay astride the vital sea route to India, the heart of imperial power in the 19th century), would be a feather in all their caps and would ensure high honors and glory for the remainder of their lives. First there were the small matters of the independent white republics and a few lingering independent black kingdoms to be cleaned up…

Well, one thing led to another and this little scheme led to thousands of dead British and Zulus, but in the end after a very expensive war an unhappy Colonial Office was presented with a conquered Zulu kingdom – and at the same time the geniuses in charge in Natal had stirred up the Boers. As part of ginning up a conflict with the Zulus, the British had investigated Transvaal’s finances deeply and found that the little government was effectively bankrupt. Furthermore, it was entirely unable to keep its population from preying on the Zulu kingdom and continually seizing Zulu land along the border (it was this land dispute that had led to the overthrow of Cetshwayo’s kingdom, in the end). Even as the colony was gearing up to invade Zululand, in 1877 they also proclaimed that Transvaal was formerly annexed to the British Empire since it was manifestly incapable of governing itself.

The Boers protested, of course, but for the moment refrained from violent resistance. No one was eager for war, and besides, as long as the Zulu kingdom existed they were a threat (especially after the Zulus massacred the poor bastards in the first British column over the border). But after the fall of the Zulu kingdom in 1879, well, the external threat was gone, but the hateful British dominion remained…

So in December of 1880 the Boers revolted and the First Boer War ensued.

It was a little enough affair – the massive British army that had conquered the Zulus had already been dispersed back to the four corners of the empire, and the tiny garrisons left in South Africa were completely surprised when the Dutchmen took to arms and began laying siege to the little forts filled with redcoats. The local British commander, Sir George Pomeroy Colley, a veteran of the Indian frontier and the Zulu War, sternly ordered the Boers to lay down their weapons, and, without waiting for a response, gathered up his little field force of about 1,000 men – less even than Chelmsford had at the battle of Isandlwana – and set off to invade Transvaal.

Well, the invasion of 1,000 redcoats with no familiarity at all with South Africa, up against an equal number of Boers, who were perhaps the finest light infantry in the world and knew the country better than the backs of their own hands, went about as well as you might expect. The British had their nose bloodied in two successive engagements before a truce was called to negotiate peace. Colley would have none of these “negotiations” with jumped up colonials, though, and seized a strategically irrelevant hill in the main pass from Natal to Transvaal – Majuba Hill. The indignant Boers kicked the British right the fuck back off the hill, the canny marksmen actually stampeding the regulars down the hillside (shooting Colley dead for good measure as he tried to stem the rout) and inflicting on the British their most humiliating colonial defeat since the American Revolution (Isandlwana, after all, had been a heroic last stand, not a rout).

The humiliation at Majuba Hill, 1881

Faced with yet another expensive-ass war in South Africa, which they still did not want, Colonial Office finally put its foot down and refused to scramble the imperial army back into the Natal backcountry so soon after leaving it. A peace treaty was signed early in 1881 and the Boer republics were again acknowledged to be independent.

A few short years later, in 1884, at the Witwatersrand in the little village of Johannesberg, the largest gold deposit in the history of the world was discovered, and everything in South Africa changed forever.

Part III: Descent to war

Quote

The Jameson raid was the real declaration of war in the Great Anglo-Boer conflict…and that is so in spite of the four years’ truce that followed…the aggressors consolidated their alliance…the defenders, on the other hand, silently and grimly prepared for the inevitable. – Jan Smuts, 1906

The Rand

In South Africa, the official unit of currency is the Rand – about 15 Rand equals one US dollar. This is not an homage to the famous purveyor of Objectivism and a celebration of South Africa’s rugged individualist spirit. No, the name comes from the Witwatersrand – the White Water Ridge, in Afrikaans – that is the foundation of South Africa’s wealth. In other words, to this day South Africans trade in “the Ridge.”

Gold had long been known to exist amidst the vast spaces of the Transvaal, but the reef uncovered in 1886 at Witwatersrand was the largest in history. Overnight, the Transvaal Republic went from a loose confederation of ranchers and farmers to one of the richest states per capita in the world. The gold fields, which lie just 30 miles south of the capital at Pretoria, soon attracted adventurers and investors from all over the world, seeking their fortunes in the boomtown of Johannesburg. The revenues of the Boer government exploded from 154,000 pounds in 1884 to over 4,000,000 by 1899, the year the war broke out. Practically overnight, the two little Boer republics went from worthless stretches of veldt not worth the expense to Britain to conquer to some of the most valuable real estate in the world.

The immediate source of tension and ultimate casus belli was the uitlanders – the outlanders. So many workers, foremen, capitalists, speculators, profiteers, merchants, drivers, prostitutes, thieves, and others descended on Transvaal to join in the gold rush that the Boers, scattered and independent as they were, quickly found themselves outnumbered in their own country. Now, they could have banned immigration, of course – but then who would work the mines? The gold mines required heavy capital investment and technical expertise, which the rural farmers of Transvaal did not have. Thus, the a conundrum – in order to exploit their windfall, they were forced to risk the very independence they had trekked thousands of miles and fought two wars to gain.

Still, the Boers tried their best to thread the needle. The uitlanders could come, but they were not admitted to citizenship. The years of residency necessary for burghership and the franchise were raised from one year to five, then to nine, and then to fourteen, as still the uitlanders poured in. Soon, the large population of foreigners began to agitate for political rights, petitioning the Transvaal government and also the British crown for redress – thus throwing the ambiguous political status of the Boer republics into stark relief.

Paul Kruger, chief of the Boers

Paul Kruger, the President of Transvaal, knew he was sitting atop a volcano. Kruger was an Afrikaaner born and bred – as a young boy he had accompanied his family on the Great Trek, tending the herds and the wagon as they made their way across the veldt, battling the Africans, the animals, and the wilderness itself to carve out a home free from British domination. Kruger had fought at the battle of Vegkop against the Matabele Zulus and had shown his flair for diplomacy, leading the Boer delegations to London in 1880 that had won reluctant British political recognition. He had thought his struggle won after the revolution in 1881 – but now the gold mines cursed him with abundance.

The uitlanders contributed the vast majority of his tax revenue, yet they had no rights within the country. To expel them was practically impossible, and would kill his golden goose besides. Yet as the decade turned from the 1880’s to the 1890’s, the tension continued to grow, egged on by avaricious politicians across the border in British South Africa like Cecil Rhodes. By the mid 1890’s Rhodes was even resorting to subterfuge and covert operations, sponsoring a small group of uitlanders with guns and money to slip over the border and foment rebellion against Kruger’s government. (to be fair, Kruger had earlier dismissed peaceful uitlander protests by sneering, “Protest! Protest! What is the good of protesting? You have not got the guns, I have!”, so really he was asking for this).

The raiders, led by one Leander Starr Jameson, massed about 500, and rode from the border of Zimbabwe northwest of Pretoria for the capital, confident just as John Brown was forty years before that the oppressed people in whose name he rebelled would rise to arms and join him in overthrowing the tyrannical regime. The raiders failed to cut all the telegraph wires at the border, though, and the alarm quickly reached the Boer authorities, who raised a commando to confront the invasion, at the same time acting quickly to quash any unrest in Pretoria or at the Witwatersrand mines. The Jameson raid ended in dismal failure as Jameson’s entire party was captured after a brief skirmish.

Henceforth things quickly fell down the slope towards war. The embarrassed imperial government denounced the conspirators, disavowed all knowledge, and chucked the British citizens involved into prison (well, nobody important like Rhodes, of course). The Transvaal Boers, though, seeing which way the wind was blowing, grimly began to import arms and ammunition and signed a treaty of alliance with their kinsmen in the Orange Free State.

The British starkly insisted that the Transvaal was not, in fact, an independent state, claiming that the two treaties with the republic – the one in 1852, the second in 1881 after what would now be known as the First Boer War – had recognized imperial suzerainty over the Dutch farmers. The Boers, by contrast, argued that any suzerainty had been voided by the treaty that concluded the 1881 war and that they were and of right ought to be a free and independent state.

The table and chairs of the Bloemfontein Conference, displayed in the Anglo-Boer War Museum in Bloem (not my photo, the museum doesn’t allow photos inside).

By the autumn of 1899, in late May, the two adversaries – the British Colonial Office represented by one Alfred Milner, the Transvaal Republic by President Kruger himself – met in the Free State’s capital Bloemfontein in an effort to hammer out their differences. Unfortunately, the gap was unbridgeable. Milner demanded that the Boers grant the uitlanders the franchise, that they use English in the meetings of the Volksraad, and that all laws passed by the Volksraad would have to be approved by the British parliament. But of course, for Kruger to grant this would be to abandon all hope of Boer independence forever. Kruger offered a compromise, offering to reduce the time to franchise down to seven years for the uitlanders, but was refused. The conference broke up by June 5 with no agreement reached.

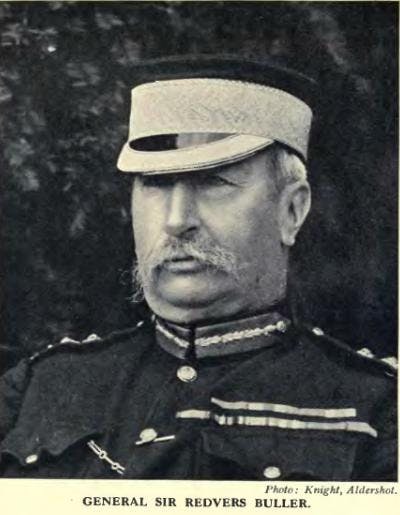

Both sides now knew that war was inevitable to settle the issue, but both sides needed a few desperate final months to prepare. On the Empire’s part, South Africa was once again defended by only a tiny colonial force, mostly concentrated in Natal, about 12,000 men total. Most of the large British army was concentrated in India, and a good part of that was unavailable for service outside the subcontinent – the Russians always needed watching, the Northwest Frontier was in perpetual turmoil, and besides, transferring Indian troops to fight white men would look ghastly to the rest of the world. Still, the British were able to prise loose about 50,000 men out of their total 250,000 soldiers available and transfer this reinforced army corps of three divisions under General Redvers Buller to South Africa. The corps would arrive in late September or early October, the start of spring.

General Buller, one of our chief personalities.

The Boers, meanwhile, could put about 50,000 men in the field between the two republics, with maybe 10,000 more available as mercenaries or from Cape Dutch rising in their support. However, they needed to wait out the southern hemisphere’s winter, for the grass on the veldt to bloom and provide their mounted infantry with sustenance (the horses, not the infantry, in case that was unclear). Meanwhile, they continued to buy up all the modern guns, including artillery pieces, and accompanying ammunition they could. By late September, with the corps’ arrival in South Africa imminent, the Boers knew they were out of time. With the British preparing to issue an ultimatum demanding the Boers disarm and surrender the franchise (as soon as their reinforcements were landed and organized), Kruger decided to pre-empt them. He issued an ultimatum of his own on October 9, 1899, demanding that the British remove all troops from the border with Transvaal (practically there were none), to remove all reinforcements that had arrived in South Africa in the previous year, and to turn around all contingents at sea and return them whence they came. The empire was given 48 hours to comply. Colonial Office predictably refused to be dictated to by the tiny backwater republic.

Two days later, on October 11, the Transvaal and Orange Free State commandos crossed the border and the Great Boer War officially began.