Part II. The Campaign

For appropriate mood music, have this video open and playing as you read:

Cetshwayo had no desire to fight the British. His uncle, King Dingane, had gotten his nose badly bloodied by Boer settlers 40 years before and had been assassinated for it. Cetshwayo knew that his impis would probably fare similarly in open battle. However, the British ultimatum was carefully couched so that he would have no choice but to refuse – especially the demands that he accept a British resident and disband his armies.

Zulu warriors, 1879 (note the red cloths tied around arms and heads – that indicates that these Zulu were actually NNC fighters. More on them later).

The Zulu army was the backbone of the kingdom’s society. It was not a professional military force, but rather a permanently maintained militia. Every Zulu man was recruited with others of his age cohort and formed into a regiment (or amabutho). These were a permanent establishment through the decades of his life – the amabutho lived together, trained together, worked together, and fought together year in and year out. The result was a force of highly cohesive, veteran amabutho.

They were well-armed for an African tribe, much better equipped than the Xhosa the British were used to fighting further south along the borders of Cape Colony. Forgoing missile weapons, the Zulu were armed with the iKwla, a short stabbing spear very similar in function to a Roman gladius. In another parallel with the Romans, the Zulu carried a five-foot long leather shield, which could deflect thrown missiles as well as being very handy in hand-to-hand combat.

Life in the amabutho was strictly regimented. Zulu warriors were required to be celibate* until the men were given permission by Cetshwayo to marry en masse. Until a warrior had ‘washed his spear’ in the blood of an enemy, many rights and privileges were denied to him. And, of course, the king retained right of arbitrary execution over any of his subjects who placed a toe out of line. Thus, the amabutho were extremely motivated and disciplined in battle – as the redcoats were shortly to discover.

Tactically, then, the Zulu were very dangerous in open battle, quickly closing to deliver shock attacks rather than reliant on missile skirmishing. Though the command and control system of the amabutho was rudimentary at best, the Zulu army attacked on a well-rehearsed pattern, the “horns of the buffalo”. Two younger amabutho would circle right and left of the enemy, forming the horns, then turn and drive the enemy on a central amabutho of more experienced warriors – the head. The wizened veterans of many campaigns formed the reserve, or loins, closing for the decisive final attack.

Strategically, the Zulu army was light and mobile, able to rapidly cross the rough terrain of Zululand and approach enemies virtually undetected. The men lived off the land, with virtually no baggage – camping and cooking gear was carried by the umbidi, the “little bees”, young boys who followed the army as best they could and joined their fathers and brothers in camps every night. The model Zulu war, then, saw army rapidly march out (the Zulu could run, barefoot, over 20-30 miles a day), find the enemy, and then fall upon him in a single decisive annihilating battle. The amabutho, as a militia force, would then disperse back to their homes.

The weaknesses of the Zulu system were several (apart from the technological disadvantage Cetshwayo faced). First and foremost, they were a militia. That meant that the warriors were also farmers, and in January they were urgently needed to gather in the harvest or the Zulu would starve. Furthermore, the army had no logistical system whatsoever – once the local area was eaten out, the army would be forced to disperse. These two factors meant that the army had no staying power – it had to win quickly, in a short campaign, or else be defeated. Tactically, however formidable the horns of the buffalo were, it was predictable. There was no hierarchy of rank in the Zulu army – amabuthos were led by their particular officers, and the army as a whole typically had a royal family member overseeing it, but there was no well-defined pyramidal structure as in Western armies. Zulu led more via prestige, and it was common for amabutho to ignore orders they felt disinclined to follow. Thus, the Zulu fought more or less headlessly, the army working through its tactical evolutions mechanically. They had a difficult time adapting to changing circumstances, or altering their tactics to try other approaches.

This was the system the BRitish demanded Cetshwayo disband, which of course he could not. The amabutho gathered every year and were used for public works projects, campaigns against hostile neighbors, or to enforce his writ within Zululand. It was the backbone of Zulu society – it could not simply be dismissed with a wave of Cetshwayo’s royal hand! Still, the Zulu king knew a war with the British was unlikely to be won, and he was desperate for a diplomatic solution. So, when the ultimatum was delivered, he agreed to give up the demanded hostages required by Frere, and to pay the fine in cattle, while asking for more time to negotiate a solution to the other demands. When that was refused, Cetshwayo began to muster his forces at Ulundi, his capital.

Knowing that the army could only stay in the field a short time, and needing an early decisive battle, Cetshwayo opted to keep the army close to Ulundi at first. He had excellent spies from renegades on the far side of the border, in Natal, and was well-informed about the British plan. The whites were gathering in several armies all along his border, but where did they intend to invade first? Which column was the most dangerous? When that question was answered, he would unleash his amabutho and crush the invaders, driving them out of Zululand. That done, he would then turn and defeat the other invading forces in detail.

Skirmish at Sihayo’s Kraal, January 12, 1879

The answer came on the 17th of January, 1879. Word came to Ulundi from Sihayo, the chief whose seizure of his renegade wives had provoked the war. His kraal, near Rorke’s Drift, where one of the British armies was gathered, had come under attack by the redcoats and he was fleeing with his people towards Ulundi. The action at Sihayo’s kraal settled Cetshwayo’s mind, and he ordered the army to march to the southwest, find the red-coated soldiers, and destroy them.

There is a broad valley that runs from Ulundi through the hilly terrain of Zululand almost all the way to the Buffalo river, the border with Natal. It forms a highway straight from the capital to one of the only fords over the river – a drift, in South African parlance. This particular drift was named after a missionary who had set up a station nearby, James Rorke – hence, Rorke’s Drift. The road from Rorke’s Drift crossed through difficult, hilly country, before emerging near the outcrop of Isandlwana and running through the Valley of Kings to Ulundi. Accordingly, it was one of the main routes of invasion of Zululand, and it was down this valley that the Zulu army moved over 3 days, quickly drawing near to Isandlwana.

The valley near its exit at Isandlwana, January 2022

On the night of the 20th, the Zulu commander, Ntshingwayo, a relative of the king, stood on a broad hill looking west. Isandlwana, a lonely outcrop of rock shaped like a sphinx, was visible in the distance – and below it the slopes were studded with white-canvas tents. The British army was in sight.

Ntingshwayo had a choice. To his left, a line of rocky hills extended south and west towards the Buffalo river. It was difficult terrain for the British to operate in, and the hills would shield him from view should he strive to invade Natal. It was also populated with several small villages that would provide food for his army, which was rapidly eating through its rations. However, Cetshwayo had expressly forbidden Ntingshwayo from crossing the border, instead charging him with attempting to negotiate a peaceful solution with the British and acting only in self-defense. So, he had no reason to try and invade the whites’ territory. To his right, across a broad valley, was another ridgeline – more broken, hilly terrain. It was less well-populated nad it would be more difficult to supply his men there, however, it would let him approach the camp on the slopes of Isandlwana more closely.

Ntingshwayo decided to avoid the southwest, not trusting all the locals who lived there, and instead swung his men across the valley to the north, bringing to the banks of the Ngwebeni stream just behind the plateau of the same name, by the afternoon of the 21st. He intended to rest his army there through the 22nd and then at dawn on the 23rd seek battle with the British, assuming no diplomatic solution had been found.

In the event, the British superseded his plans.

—–

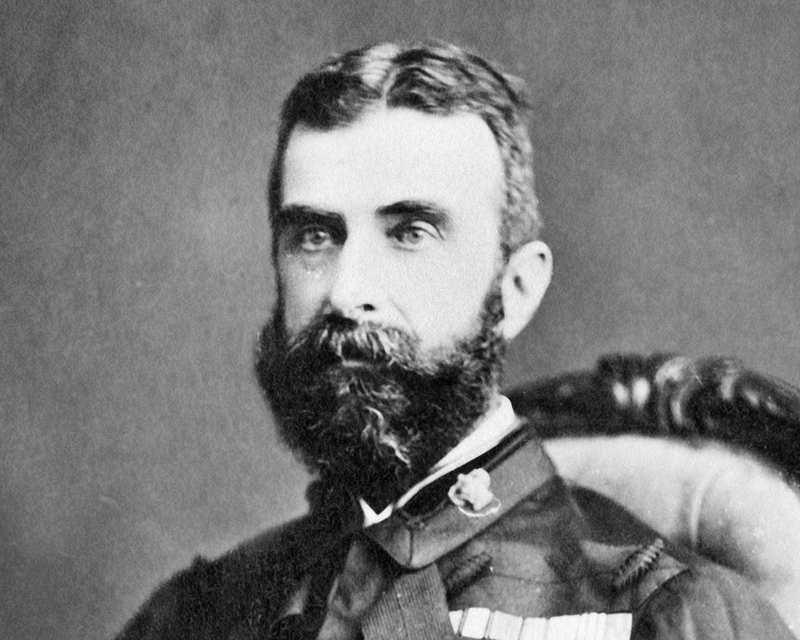

Lord Frederick Thesiger, Baron Chelmsford, commander of all imperial British forces in southern Africa, had had an undistinguished career thus far. One of those soldiers regrettably born after the great war of his times (12 years after Waterloo), he had served solidly in the Crimea and in India but with little opportunity for glory. Since plodding through the cursus honorum of the British Army to commander in Africa, he had successfully fought a minor bush war with the Xhosa. It was that experience that formed his plan of campaign for the conquest of the Zulus.

Chelmsford did not fear meeting the amabutho in battle – quite the opposite, in fact. He had only about 7,000 regulars distributed in 9 battalions in all of southern Africa (the War Office had refused to send more troops to what was in essence a police garrison, worried [rightly] that reinforcements would encourage Frere to launch his damned war), but they were armed with the highly reliable and effective breech-loading Martini-Henry rifle. Disciplined fire from a battalion of redcoats would lay down a curtain of steel capable of warding off any number of iKwla**-wielding natives. Thus, open battle with the Zulu was to be preferred, letting him settle the business in a bloody afternoon. However, he would have to make sure that his regulars were well-supplied with food, water, ammunition, and other essentials for war in trackless Zululand – a formidable task. Each battalion, for example, consumed a ton of food per day, which would have to be hauled with them. Ammunition would have to be carried. Water was difficult to find in the country, and so he would need to invade in the wet season, when the dry watercourses (dongas, in South African parlance) would flow. All of this would have to be hauled with him, and his central column alone required more than 300 wagons

In turn, the wagons could create problems. Each would be hauled by a team of 16 oxen – sturdier, more reliable than a horse, and capable of feeding itself off the local forage, oxen were the ideal choice. But oxen are slow, and stubborn, and are not bred for work – to keep each team in harness continuously would see all his beasts dead before he’d made it a tenth of the way to Ulundi. No, the oxen would need to rotate, one day on, two days off – so each wagon would need not 16 but 48 beasts to haul it, meaning one column alone would require damn near 15,000 cattle to supply it. So, unlike the Zulu, any British column would be hideously slow on the march – and the slower they went, the more supplies they would consume, the more of the wet season they would lose, exacerbating the water problem, etc.

The supply problem fed into Chelmsford’s other great fear: that the Zulu would not fight him. The Xhosa made war via ambush and subterfuge, avoiding open battle and opting to raid British supply lines and frontier farmsteads. The Zulu, with their legendary stealth and mobility, might avoid his army entirely, slip around behind, and go pillaging in Natal as they had the generation before. They might even get as fars Pietermaritzburg, or Durban! With a war on thin enough political ice as it was, such a move might be a deathblow to his and the politicians Frere & Shepstone’s careers (and also literal death to lots of innocent colonials, but we’re focused on what’s important here).

So, Chelmsford adopted the obvious strategy for invading Zululand: he divided his forces. Obviously he couldn’t mass all 7,000 troops in one weighty column and smash ahead to Ulundi. Ulundi was nothing more than a pile of rocks on the ground – it could be razed entirely by the British, but the Zulu would just rebuild it as soon as the army left. Further, one huge column would have its wagon train stretch for miles upon miles – it would be so sluggish as to be almost immobile. The amabutho would slip around it and pillage to their heart’s content. No, he needed to spread his armies over multiple routes, to lower each column’s supply train to a manageable level. Plus, he would throw his net wide, and hem the Zulus in so no matter which way they turned, they would meet one of his armies coming in. Then the British would get their bloody afternoon, shatter the Zulu armies, press on to Ulundi, capture Cetshwayo, and put an end to the business before the Colonial Office even finished its meeting trying to decide what to do about Frere.

Chelmsford had, as stated, about 7,000 British regulars to work with, infantry and light artillery for the most part. He had virtually no professional cavalry, but was able to recruit volunteers from the local colonial and Boer population. These would provide essential scouting and screening duties in the trackless Zululand. Further, he had several thousand renegade Zulu to call upon – the Natal Native Contingent, identical in arms, equipment, and dress to their brethren across the Buffalo river, distinguished only by a red cloth tied around their arms.*** All told, he had about 17,000 men to confront the Zulu’s estimated 40,000-50,000 strong army (impi, in Zulu).

The good baron split his army into five. I Column, with one regiment of regulars, would invade up the coast road from Durban through Eshowe and approach Ulundi from the southeast. His main force, which Chelmsford assumed personal command of, III Column, would strike from the main crossing at Rorke’s Drift over the hilly border terrain and then straight up the valley of kings to Ulundi from the southwest. A final invading column, IV Column, would march from the Transvaal in the north and come upon the capital from the northwest. Meanwhile, one column of volunteer horse under one Colonel Durnford (II Column) would patrol the Natal/Zululand border, and a second (V Column) would keep an eye on the border between the Boer Transvaal republic and the Zulus – as much to keep the Boers from getting any funny ideas while the British had their hands full as to protect them from Zulu raids.

It is the fate of the central column under Chelmsford that has become legend. Its core was two battalions of the 24th Regiment of Foot, about 1300 regulars, all told. They were supported by various companies of mounted volunteers, Natal mounted police, etc, providing about 300 horsemen, and more than 2500 warriors of the 3rd Regiment, Natal Native Contingent. All told, there were roughly 4500 fighting men in the column, with a further 300ish camp helpers, drivers, sutlers, etc.

Saturday morning, January 11, 1879, dawned grey and drizzly – Natal’s rainy season, although it would definitely get hot later in the day. Chelmsford’s column lurched over the Buffalo at Rorke’s Drift as Cetshwayo’s deadline expired, and the invasion officially began. The terrain immediately on the far side of the drift, although the most favorable terrain for wagons, was hardly promising – steep hills and rocky, broken terrain made it apparent that Chelmsford would have to carve a road. So, the British pitched camp and began to dig.

On the 12th, the NNC, supported by 4 companies of the 24th (in case they got into trouble), launched an attack on Sihayo’s kraal. Sihayo was the chief who had provoked the whole war, in British eyes, by his repeated violations of the border. His kraal was sited in a rocky gorge just off the northern flank of the column and would need to be cleared out to secure the line of march – plus, it’d be a nice bit of first blood. The skirmish was short and easy, settling the British mind that this campaign would be more of a glorified hunting expedition than a serious battle against a dangerous adversary.

While the British crawled through the hills, survivors from Sihayo’s kraal fled to Ulundi and raised the alarm. Soon, all the amabutho were aroused and streaming towards III Column.

Isandlwana from the southeast. The British came through the small saddle on the left. The Zulu army is lurking a few miles away atop the plateau at right.

After days of difficult travel, the British army straggled around the hill of Isandlwana. This striking hill was compared to the Sphinx by the men of the 24th, who had fought in Egypt. It looked grim and ominous, looming out of the plain, but Chelmsford was not troubled by superstition. Isandlwana provided good firewood for his camp, access to water, and was in a secure location – the hill itself shielded the camp from attack to the west, and its sightlines to the east (the road to Ulundi) and south were excellent. A plateau to the north did offer some opportunities for concealment, but that was easily remedied via pickets on the heights. By the afternoon of the 20th, camp had been laid out while the wagons straggled up.

That same afternoon, Chelmsford reached the slopes of Isandlwana, staring across the same valley that Ntshingwayo, head of the Zulu impi far to the east, was even now looking down on. The baron conducted a personal reconaissance to the south and east from the hill, and though he saw several villages with Zulu milling about, no sign of the main force was seen. He expected the arrival of the Zulu army any day now, and so Chelmsford decided to launch a major scouting effort the next day.

Meanwhile, several of the Boer volunteers in camp had approached Chelmsford and warned him that he needed to laager his wagons – that is, to pull the wagons into a ring around the camp as a makeshift fort. Generations of battling Zulus had taught the Afrikaaners that this was the only safe way to campaign. But Chelmsford could not. Laagering a small Boer kommando of a few hundred fighters was a very different proposition than laagering 5,000 of Her Majesty’s troops. His wagons were employed in hauling supplies to and from Rorke’s Drift – he did not have the numbers to spare. Nor could the ground be entrenched – the terrain at Isandlwana is hard and rocky. It would take a week to fortify the camp and the British would not be at Isandlwana a week. This was a temporary halt while supplies were got up and the terrain ahead scouted, nothing more. Remember, Chelmsford was on a time limit. He had to reach Ulundi before his supplies and the wet season gave out, and his advance was already too slow. So, Isandlwana remained unfortified.

The road from Isandlwana to Rorke’s Drift. Though the distance is short – the mission station is just behind the hill at center – the rocky & hilly terrain made the British advance agonizingly slow.

The baron’s main concern was his right flank. The plain in front of Isandlwana was boxed in on three sides by hills and ridges – to the north, a few miles to the east, and to the south. The hills east and south of the plain would screen any Zulu force attempting to slip past III Column and invade Natal by one of the lower drifts. The possibility of invasion constantly occupied his mind. Before dawn on the 21st, Chelmsford dispatched Major Lonsdale with nearly his entire NNC contingent – more than 2,000 men – to scout to the south and east and seek out the main impi. Then, he followed up by detailing Major Dartnell with 150 mounted men from the Buffalo Border Guard, the Natal Mounted Police, the Newcastle Mounted Rifles, and Natal Carabineers – nearly all of his light cavalry – to ride due east and then turn and sweep south to meet up with Lonsdale’s renegade Zulus. Thus, the entirety of the British scouting effort – including all of its light infantry and cavalry – was directed in entirely the wrong direction. The main Zulu army, quietly resting in the valleys to the north of Isandlwana, was entirely undetected on the 21st.

British scouting efforts on the 21st and 22nd. Isandlwana is just to the left of the white square at left center (the British camp).

The area to be scouted was immense, and the terrain very difficult. Dartnell led his cavalry over the hills and out of sight of camp, and very soon found himself in trouble. There were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Zulu in the hills – either warriors operating independently of the main army, or, as some allege, amabutho deliberately planted there by Ntshingwayo to draw off British attention. However it was planned, the Zulu alarmed Dartnell, who several times nearly found himself surrounded with his horsemen. He linked up with the NNC under Lonsdale coming up from the south, and sent a slightly shrill message back to Chelmsford, announcing that he had found the main Zulu column and was forting up for the night.

Now, Dartnell and Lonsdale had both been ordered to return to camp by nightfall – Chelmsford certainly didn’t want his light infantry and cavalry to be caught out there alone without the support of the regular line infantry. But the message came so late in the day that there was little the baron could do – it was already growing too dark for the men to return to camp in the light, and straggling over the hills in the utter darkness of Zululand at night (believe me, in my experience there you can’t see your hand in front of your face without a light source – and the night of January 21 was a new moon!) was a recipe for ambush and disaster. Irritated, he granted permission for the men to bed down on the far side of the hills.

At 1 in the morning on the 22nd, a further messenger arrived from Dartnell. By now on the edge of panic, Dartnell and Lonsdale reported hundreds of campfires visible in the darkness, a patrol was nearly cut off by roving Zulu in the night, and twice the skittish NNC had stampeded from imagined night attacks. Dartnell begged for infantry support in the morning – if Chelmsford sent reinforcements he could be certain of his battle with the main Zulu army. Perhaps tired, short on sleep, or simply having his expectations confirmed, Chelmsford prepared for a dawn march.

What the terrain looks like on the ground – looking east from the British camp. Dartnell and Lonsdale are camped beyond those hills on the right. The Zulu, of course, are behind the ridge on the left.

When day broke on the 22nd of January, the baron moved out. He took with him the 2nd battalion of the 24th – half his redcoated infantry. He left the remainder, the 1st battalion, to guard the camp from any raiders lurking about, and sent word back to Dunford with II Column at Rorke’s Drift to come up and support the camp. Then he set off to seek the enemy and decisive battle.

Thus, at about 8 in the morning, the British army was scattered all to hell and back around Isandlwana. In the furthest eastern advance, Dartnell and Lonsdale crouched in their temporary bivouac, surrounded by imagined foes with the light cavalry and native auxiliaries, roughly 1,000 men. Marching to their relief was Chelmsford with half his regular infantry and more natives, nearly 2500 combatants. Encamped at Isandlwana itself was his other battalion of infantry, camp guards, and sundry followers totalling about 1100 defenders. Hastening up from Rorke’s Drift a few kilometers away was Durnford’s column of a few hundred cavalry. Finally, lurking just to the north of the main camp, and as yet undetected, was the main Zulu army of about 25,000 men.

Everything was in place for one of the greatest debacles in British colonial history.

*more or less

**The British wrongly dubbed them assegais

*** In the heat of battle this distinction was often overlooked by jumpy British regulars