Note: The next couple of posts are re-posts of writing I did elsewhere. I thought it would be sensible to rehost it and revive my blog a bit, doing a bit of historical writing.

I recently had the chance to visit another obscure battlefield in a far corner of the world, and so I thought I’d repeat the effort. Read on for a tale of wicked invasion and bloody battle, of greed and ambition running into defiant courage, of man’s folly and incompetence – but also his heroism.

The Battle of Isandlwana

Today, sheep graze in the shadow of the hill of Isandlwana.

The sphinx-shaped hill is in far-distant country, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest major city of Durban, in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. To get there, I had to wind up and down hills on gravel roads littered with obstacles – massive potholes capable of swallowing a small car, herds of cattle wandering to and fro on the ‘highway,’ the omnipresent taxis careening past the switchbacks. It’s a hair raising journey, and nothing at all like the quiet and easy train ride out to remote Sekigahara, the last obscure battlefield I visited.

Life in Zululand, or KwaZulu in its own tongue, carries on today much as it has for over 200 years. The Zulu still live in villages of small rondavels gathered around the chief’s house. The main source of wealth is still livestock, left free to graze where it will on the rolling hills. The hills themselves are largely untouched by agriculture, outside the massive eucalyptus tree plantations, since most of Zululand is game reserve. In the royal palace, the king of the Zulus still carries out his duties – albeit today the succession dispute rocking the royal household is now fought in the courts in Pietermaritzberg rather than with spears out in the hills.

The valley of Isandlwana is no different. The distinctive hilltop looks over a plain dotted with Zulu villages. Young boys chase goats around the gravel roads, women carry water from the sparse wells in this dry country back to their rondavels, and scarcely a car ever passes through the pastoral landscape (no surprise, getting here with all 4 tires intact is a hell of a task).

Isandlwana from the Nqutu ridge, January 2022

As I arrived on the ridgeline overlooking Isandlwana on a sunny January day (this time not alone, as I was in Sekigahara, but somehow having convinced my wonderful wife to trek with me hours out into the African wilderness to see this field), I saw the Zulu children playing on the slopes of the hill. It’s grassy, with a few scrub trees and bushes, and rocky, the entire landscape dotted with boulders. I wondered if the kids recognized the significance of where they were playing – for on the shoulder of Isandlwana there are visible dozens upon dozens of small white stones piled into cairns.

Every single cairn marks the grave of redcoated soldiers. Every cairn is the final resting place of one of the men of the 24th Regiment of Foot. Nearly 124 years ago, the 24th was wiped out on the slopes of this hill by the armies of Zulu king Cetshwayo, in one of the worst colonial disasters ever to overtake British arms. This quiet valley and the cairns of stones, ignored by the young people playing among them, is the scene of the greatest victory in Zulu history – and the last gasp of an independent people before conquest, subjugation, and decades of apartheid.

Over the next few days in this thread I would like to share the story of what happened here, and what came afterward.

I. Strategic Background

The British Empire in 1878 was indisputably the premier power of the world. From the small, rain-swept island off the coast of northwest Europe, conquering fleets and armies had issued forth time and again to plant the flag in the wilds of North America, across the Caribbean, to hold the Mediterranean in a vise at Gibraltar, Malta, and Egypt, to throw open the gates of China’s Celestial Empire, to bring all of the Indian subcontinent under its sway, to seize the entire continent of Australia, and, lately, into the deepest heart of Africa. The Royal Navy held this sprawling, disparate empire together with hundreds of the most modern warships in the world, far outclassing any potential rival, and the Royal Army, though small, was perhaps the most disciplined and professional infantry fighting force in the world.

But for all that, this empire was a patchwork one. There were simply too few British gentlemen of quality to completely administer the hundreds of princely states, kingdoms, renegade republics, penal colonies, frontier towns, garrison isles, and dependencies in the vast territory that swore allegiance to Victoria. Instead, the British ruled with a light hand, dependent upon local allies and compliant puppet rulers to ensure London’s will was done.

Southern Africa in 1879. Natal and Zululand are at far right.

Nowhere was this patchwork more evident than in the British-ruled areas of southern Africa. A half-dozen major states dotted the area, all more or less officially ruled by Her Majesty. In reality they were an unruly, squabbling pack of siblings as inclined to fight each other as to trade. The Cape Colony and Natal were built around their magnificent harbor cities of Cape Town and Durban, respectively, and were the most British in character. In the high veldt, the stubbornly independent Boers had established their own republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State, though they nominally accepted British suzerainty.* In between were dotted African statelets and kingdoms – Lesotho, Eswatini, Transkei, and, significantly, Zululand. The man appointed to oversee this nonsense, Theophilous Shepstone, was officially titled the Secretary of Native Affairs in Natal. Basically he was the poor sap in charge of handling all negotiations between the Boers, the Zulu, the Sotho, the Swazi, the Khosa, and a dozen other tribal groups in South Africa.

Ten years before our story begins, in Canada, the British had been able to weld a similarly disparate group of colonies into one Dominion. Quebec, Ontario, the Maritimes, and even the sparsely settled western frontier provinces had been federated and placed under unified rule in Ottawa. A similar scheme might ease the British headaches in South Africa, a land they had never really intended to rule.** And so in 1876 a new High Commissioner for South Africa was appointed: Sir Bartle Frere.

Sir Henry Bartle Frere, chief architect of disaster

Frere’s mission was simple: To peacefully unify South Africa under a white minority rule, while the black majority provided labor in the lucrative sugar plantations and diamond mines springing up around the country. The blacks would extract wealth to help swell the coffers of the Empire, the whites would keep the peace and allow London to more or less ignore that distant corner of the world, and Frere would find himself the first Governor-General of the united South Africa as a feather in his cap. The scheme was simple and lucrative.

The one sticking point was the Zulus.

The Zulu kingdom was the most powerful African state in the history of southern Africa. The history of that land is too detailed to get into here, but suffice to say that Zulu, under their king Shaka and his powerful army, had carved an empire in blood out of the rolling veldt in southeast Africa. They had defeated all rivals and driven all their neighbors out of the kingdom in the Mfecane, the “Scattering.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mfecane). However, in one of those twists of which history is so fond, into this vacuum, this desolated wilderness devoid of people due to the Zulu blood wars, had stumbled probably the most unlikely group of people imaginable in southern Africa: white farmers, Dutch nomads, wagon-riders with their entire homes and families in tow. The voortrekkers, on their Great Trek fleeing British oppression in the Cape, had come upon the Zulu.

The Zulu and Boers introduce themselves to one another

Well, one thing led to another, wars and glorious battles were fought, treaties were signed and broken, there was betrayal and bloody massacre, murder and revenge, heroism and cowardice on both sides, but when the dust had settled the Boers and the Zulu had forged out a peaceful-ish coexistence, with the Boers in their republics of Transvaal and Natalia on one side and the Zulus in kwaZulu, “Zululand,” on the other. Then the British had promptly annexed Natalia with its splendid port at Durban and proclaimed the new colony of Natal.

Anyway, as the British colony in Natal grew and prospered from its foundation in the early 1840s to the late 1870s, the Zulus remained a lurking menace to the north. Natal was a fabulously fertile and green country, home to many and growing lucrative sugar plantations, but the whites who came to grow sugar and grow rich had a serious labor problem. Whites had no desire to come and work the malarial fields. Indians were tempted over from the subcontinent and alleviated some of the issue – to this day Durban is the largest Indian city in the world outside India itself – but the main source of manpower was always the Zulu.

However, the Zulu kingdom had forbidden its men to work with the British. Anyone caught working south of the border was declared a traitor and could expect brutal execution if he returned home. That tended to hamper recruitment efforts. Even so, some men would slip across and work for a while – but the idea of long-term commitment did not appeal. Farmers would wake up in the morning to discover that their field hands had carefully considered the matter and come to the conclusion that they’d earned enough money – and had lit off back home in the middle of the night, to slip home with their guns or their cattle (valid forms of payment in a kingdom not really accepting of cash currency) and take up their old lives.

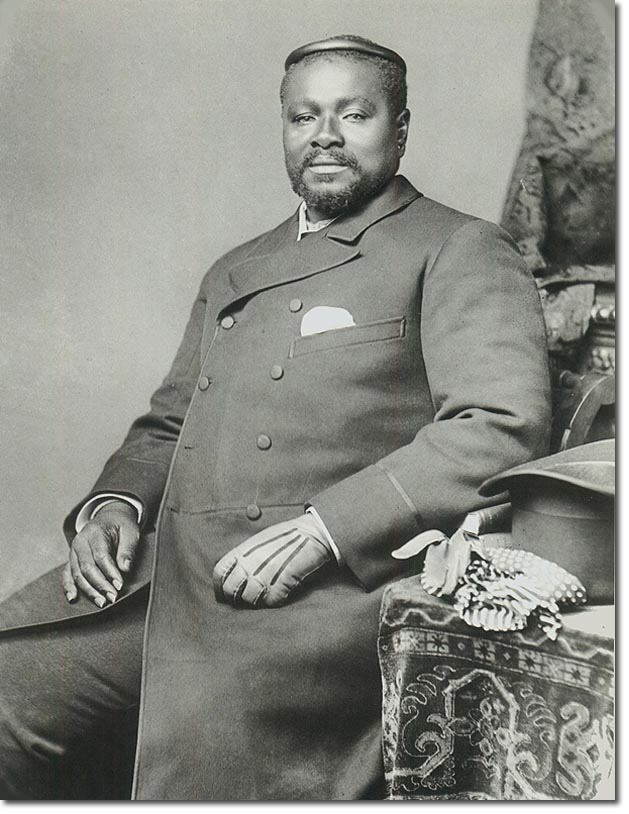

Cetshwayo, King of the Zulu

Even worse, the Zulus, as a powerful, independent African kingdom, was a terrible example to all. Why, other blacks would look to the Zulu and think that perhaps they also could rule their own states! Perhaps even stand up as equals to the white man. The king, Cetshwayo, by his very existence made negotiations with blacks all across southern Africa immensely more difficult. As Shepstone put it, “”Cetshwayo is the secret hope of every petty independent chief hundreds of miles from him who feels a desire that his colour shall prevail, and it will not be until this hope is destroyed that they will make up their minds to submit to the rule of civilisation”. It was a horrifying thought, and Frere and Shepstone were resolved to do something about it.

Now, Home Office in London had strictly forbade him from getting any damn-fool ideas in his head about war with the Zulus. The empire had concerns enough in Eastern Europe and India and was not at all interested in yet another frontier war in Southern Africa with a people with unpronounceable names and funny clothes. Frere received these instructions, nodded gravely and said he understood, and went about provoking a war behind his bosses’ backs anyway. Hell, the whole thing would be over before London got wind of it anyway. Trot the boys up to the border, have one short sharp battle with the fuzzies – put the fear of God and the Martini-Henry rifle in ‘em – grab the Zulu king and Bob’s your uncle. What would Home Office do, apologize and give Zululand back?

To sum up: The British Empire wanted to unify South Africa to solve its administrative and labor problems, but they did NOT want an expensive and unnecessary war to get it. The local bigwigs, Frere and Shepstone, however, figured they could sort things out before the hippy pacifists in London could object to the favor they were being done.

So Frere, with the connivance of Shepstone, in 1878 began to manufacture an excuse to invade and annex Zululand. Now, this is Africa – deep in Natal, the borders got fuzzy, rivers changed their course or ran dry in the winter, and there’s for damn certain hardly any good maps. So, very helpfully for Frere and Shepstone, no one was quite certain where the border between the Zulus and Natal actually was. A few incidents were seized on – the Zulus dragging a fugitive wife of one of their chiefs from their refuge in Natal back over the border to be treated in the usual Zulu fashion, ie, brutally executed, then the Zulus doing exactly that thing again, and a third incident involving a lost surveying party – and the two servants of Her Majesty Victoria in Durban had everything they needed for a war (if you squinted very hard): they prepared an ultimatum outlining these “grievances” to Cetshwayo, the Zulu king, rounded up a handful of other paper-thin excuses that could be seized upon and declaring that obviously the only acceptable resolution was the total disbandment of the Zulu army, payment of massive fines in cattle, and accepting a British Resident, among other things. They rode up to the border with Zululand at the start of summer, December 11, 1878, handed the letter to a few confused Zulu border guards, and dashed away. Cetshwayo was given 30 days to comply.

In the meantime, around October or November, Frere had sent a few letters by the slowboat to London, absently mentioning in his reports that he intended to get an explanation from the Zulu for the ‘outrages’ committed against Natal. London, scarcely paying attention (having sternly and repeatedly warned Frere not to provoke a damnfool bush war in South Africa), equally absent-mindedly replied not to push things too far, certainly don’t do anything like issue ultimatums or other ridiculous nonsense like that. By the time London’s reply reached Frere, oopsie, he’d already started the redcoats across the border.

Cetshwayo, when he received the ultimatum, was scarcely aware that the countdown against him had already begun. He could hardly comply, of course, since the British were more or less demanding his complete annexation, but he knew his chances in a war with the Empire were so slim as to be nonexistent. Cetshwayo desperately offered to negotiate over these “grievances” (most of which he was hearing about for the first time), to no avail. The 30 day limit expired and on January 11, 1879, the British army began crossing into Zululand in multiple areas.

The Anglo-Zulu war, war neither London nor Ulundi had wanted, had broken out mostly due to the conniving ambition of Sir Bartle Frere. He, of course, had greatly exceeded his orders, but so what? One short sharp fight and the war would be over and all London would be able to do is give him a medal for his glorious conquest.The Zulus were brave and proud warriors, but they were armed with spears and shields, against crack British redcoats. What was the worst that could happen?

*In practice the Boers hated the British – they had fled deep into the interior of Africa in an effort to escape their rule around the Cape – but with the threat of the Zulus they grudgingly accepted British ‘protection.’ It would take multiple wars over the next 25 years to fully bring the Boers into the empire.

**The British had seized the Cape from the Dutch in 1804 to keep the crucial way station out of French hands. Things had gotten a bit out of hand from there as they stumbled into the various other colonies in the area.