The hardest part of any story is beginning it. This is especially true of history. Did the French Revolution begin with Louis losing his head, or with the storming of the Bastille, or with the oath in the tennis court? Did the Cold War start with the Berlin blockade, with the surrender of Japan, or even earlier with the first Trinity Test? And the Gwangju uprising – do I begin with the students confronting the paratroopers in front of Chonnam University? With the military proclaiming martial law on May 17? With the December coup?

I suppose, if you want to be technical about it, we should start with Mireuk, without whom no one would have separated the earth from the sky by setting the sky on 4 copper pillars at the corners of the earth, and without whom no one would have created mankind (men from 5 golden insects, women from 5 silver), and where would we be then?

But I will begin, I think, where almost all modern Korean history begins: with the fall of Japan.

Korea in August 1945 was an afterthought to, well, damn near everybody.

In the west, President Harry Truman was winging his way home from Potsdam, his mind full of the problems with the war against Japan, sorting out the defeated Germany, and, more than anything else, the looming threat of the Soviet Union and the implications of the new weapon he had tested out in the New Mexico desert the previous month.

In Europe, the continent was first starting to piece itself back together in the aftermath of the great war just ended. Refugees and displaced people flooded over every nation, everyone seeking loved ones, too few succeeding. Most of the continent lay in ruins, especially Germany, now divided, occupied, and dazedly trying to guess what a post-Nazi future for the country might look like – or maybe people were just trying to survive from one day to the next, like they had every day for most of the previous harrowing decade.

In Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines, collapsing Japanese army units fought desperate, last-ditch stands against victorious Allied armies. Some men would vanish into the jungle to continue their fight there. Some would not re-emerge for thirty years.

In Manchuria, the Red Army stormed forward in Operation August Storm, brushing aside the Japanese defenders like an NFL linemen rushing a toddler. The IJA was undersupplied, demoralized, and outnumbered – the Red Army was seasoned, well-trained, well-equipped, fresh from victory over the Wehrmacht and at the height of its power and glory. The communists smashed aside the paltry Japanese defenders and stormed south for the Yalu River.

And in the Central Pacific, the 509th Composite Group, operating from the modest North Field on the sunny island of Tinian, sent a small squadron of three B-29 Superfortresses on a strike mission to southern Japan. Their names were The Great Artiste, Necessary Evil, and Enola Gay.

No one was thinking about Korea.

——-

After the destruction of Hiroshima and the surrender of Japan, the State Department in Foggy Bottom suddenly found themselves with a problem. Well, actually, they had many problems – maybe more problems than any State Department before or since has ever had to deal with. What do with defeated Germany? How to rebuild Western Europe? How many US troops shall we keep in uniform? What is our relationship with the Soviet Union? What about with every single “liberated” state in Eastern Europe? What of Greece, Turkey? What of the European empires in Africa and in Asia? What of the Nationalists and Communists in China? What of the former Japanese empire?

It was a rat’s nest of issues, old grudges, new opportunities, rivalries, hatreds, long-standing alliances now outdated, maps made obsolete…the old world had been shattered, and now it was up to Harry S. Truman, of Independence, Missouri, and the Department of State, to try and forge it anew. Letters and contacts poured in from all over the world. Greece, begging for aid in its civil war against Communist rebels. Poland, pleading not to be forgotten. The Soviet Union, wondering about the future of their wartime partnership. Some leftist nutter named Ho Chi Minh, asking for help booting the French out of their Indochinese possessions. Oh, yes, and what the hell do we do with the Empire of Japan and all its possessions?

Amidst this chaos, apparently no one had given forethought to the precise details of the disposition of the Japanese possessions outside the home islands. Korea had been discussed, but only in passing. On August 9, after Hiroshima, after August Storm, suddenly the surrender of Japan – something not previously thought to happen until late 1946, at the earliest – loomed as an imminent possibility. On the night of August 10, Allied military planners hurredly met to convene surrender procedures, to keep Soviets and Americans from accidentally (or not) murdering each other in the confusion.

As the official Army history puts it:

“Under pressure to produce a paper as quickly as possible, members of the Policy Section began work late at night on 10 August. They discussed possible surrender zones, the allocation of American, British, Chinese, and Russian occupation troops to accept the surrender in the zone most convenient to them, the means of actually taking the surrender of the widely scattered Japanese military forces, and the position of Russia in the Far East…

The Chief of the Policy Section, Col. Charles H. Bonesteel, had thirty minutes in which to dictate Paragraph 1 to a secretary, for the Joint Staff Planners and the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee were impatiently awaiting the result of his work. Colonel Bonesteel thus somewhat hastily decided who would accept the Japanese surrender.…At first Bonesteel had thought of surrender zones conforming to the provincial boundary lines. But the only map he had in his office was hardly adequate for this sort of distinction. The 38th Parallel, he noted, cut Korea approximately through the middle. If this line was agreeable to President Truman and to Generalissimo Stalin, it would place Seoul and a nearby prisoner of war camp in American hands. It would also leave enough land to be apportioned to the Chinese and British if some sort of quadripartite administration became necessary. Thus he decided to use the 38th Parallel as a hypothetical line dividing the zones within which Japanese forces in Korea would surrender to appointed American and Russian authorities.”

– Policy and Direction, The First Year, 9.

The 38th parallel, decided upon by Charles Bonesteel, who was up too late on the night of August 10th, with inadequate coffee, a smarmy State Department aide joggling his elbow for him to finish, a rotten map, and only thirty minutes to work, has stood as the boundary between North and South Korea for 75 years.

A second major problem – besides the fact that pretty much no one in the United States had ever heard of “Korea” – was that they had basically no plan in place for how to administer “their” sudden new occupation zone. The Soviets, perhaps cowed and cautious by the threat of the Bomb, placidly accepted the 38th parallel and set about converting their half of the peninsula into a glorious people’s republic. They plucked a suitable anti-Japanese guerrilla from obscurity, gave him a suitably heroic backstory, more or less made up out of whole cloth, and set him up as the Dear Leader of their new pet. Thus did Kim Il-Sung become the founding member of the present ruling house of North Korea.

The United States had no such plan. They had no shadow government in place to assume the reins, they had no Korea desk at the State Department, hell, they didn’t even know how long they’d be in the country, let alone what they wanted to “do” with it. The Navy rapidly ferried a handful of confused soldiers up from the Philippines and flung them into Seoul, where they aimlessly milled around for a few months while the higher-ups tried to figure out what the hell they were doing.

In the end, as is often the case with the United States, they settled on the first convenient man they ran across. And here is where the troubles began.

——

Korea, after quietly whiling away a sleepy couple of centuries under the Joseon dynasty, had fallen victim to early 20th century power politics. Initially a bone in the struggle between Qing China and Meiji Japan, Korea had first become a puppet, then an outright colony, of the island nation since 1910. But the Koreans had not taken the Japanese occupation lying down. Almost from the first, there was resistance, including in the peaceful southwestern city of Gwangju.

Across the country, there were uprisings, protests, strikes, and riots. In the barren and frigid northern hills near the Yalu, bands of rebels roamed around bushwhacking isolated Japanese garrisons. In the cities, Koreans frequently engaged in strikes or other forms of passive resistance to their colonial occupiers. The college students did what college students do best and wrote various Statements and Declarations of Intent, and engaged in protest marches. The Japanese responded with all the grace and nuance Showa-Era Japan is famous for.

While the myriad arrests, beatings, exiles, and outright murders failed to fully pacify the peninsula (to say nothing of apolitical monstrosities like the practice of comfort women, or Unit 731’s horrors), they did serve to more or less keep a lid on things for Japan through 1945. Many groups found it too hot to stay in the peninsula itself, and exiled themselves to surrounding nations, mostly to China, which was merrily engaged in one of its regular periods of outright anarchy and civil war*. One of these groups somewhat self-importantly called itself the Korean Provisional Government in Exile, and their Representative to the United States was one Syngman Rhee.

Rhee was born in 1875 and taught English by Methodist missionaries active in the country. He came of age just as the Japanese involvement in Korea was ramping up, and became strongly anti-Japan. In March of 1919, he joined with myriad others to instigate a gathering of students in Seoul, who proclaimed Korea’s independence. The Japanese were less amused by this than the students were, and to escape arrest, torture, and probable death, many fled to Shanghai, Rhee among them. There, his political acumen and intelligence quickly propelled him up the ranks.

Rhee’s English ability got him named Representative to the United States, and he lived there through most of the Thirties. Styling himself the Chairman of the Korean Commission to the United States, Rhee spent his days agitating against the Japanese and lobbying the American State Department for recognition and material support for Korean independence. Consumed with more important matters like the Second World War, the State Department spent most of its time, in turn, ignoring the little man from the backwater peninsula no one had ever heard of.

Until fate intervened, and suddenly the United States found itself in possession of half of that backwater peninsula and not a clue in the world what to do with it.

“The British diplomat Roger Makins later recalled, “the American propensity to go for a man rather than a movement — Giraud among the French in 1942, Chiang Kai-shek in China. Americans have always liked the idea of dealing with a foreign leader who can be identified as ‘their man’. They are much less comfortable with movements.” Makins further added the same was the case with Rhee, as very few Americans were fluent in Korean in the 1940s or knew much about Korea, and it was simply far easier for the American occupation government to deal with Rhee than to try to understand Korea. Rhee was “acerbic, prickly, unpromising” and was regarded by the U.S. State Department, which long had dealings with him as “a dangerous mischief-maker”, but the American General John R. Hodge decided that Rhee was the best man for the Americans to back because of his fluent English and his ability to talk with authority to American officers about American subjects.”

– Max Hastings, the Korean War

In other words, Rhee was an asshole, but he was an asshole who spoke English and, more importantly, he was available. So Syngman Rhee found himself shipped off from Washington and back to his home in Seoul for the first time in 25 years, where he became the primary liaison between the United States occupying authorities and the people of Korea. In essence, Rhee became the Korean government.

The years between 1945 and 1950 were the era of Translator Government in Korea. The Americans, fumbling around hopelessly in the dark, frequently leaned on former Japanese officials, who were after all fluent in the government and language of the peninsula. Understandably, this did not endear them to the people of “south” Korea, as the American half of the peninsula was coming to be known. People who could translate between English and Korean found themselves in positions of inordinate infuence, and Rhee, with his political acumen, quickly consolidated power behind himself, if not with American approval, at least with American indifference. America wanted nothing more than to be done with the funny little peninsula and get their boys back home. Its attention was always elsewhere – mostly on Berlin and Germany and the steadily growing showdown with the Ruskies. They gave half-hearted training to a South Korean “army,” which was mostly a police force meant to keep order in the peninsula and help Rhee hunt down his “Communist” opponents scattered around the South. Of course, Rhee was very generous with the term “communist” and arrests, torture, and imprisonment were par for the course for his government. Rhee also made frequent requests for heavy weapons like tanks, aircraft, and artillery, but the Americans, fearful that this “mischief-maker” would do something crazy like go haring off on an invasion of the Soviet zone to the north, refused. By 1949, all American troops were withdrawn from the peninsula, and the State Department was giving speeches suggesting that the American involvement in the little backwater of Korea was officially at end.

Unfortunately, the North had not been idle during this time. While Rhee had been playing on his position as the middleman between the USA and the people of South Korea, Kim Il-Sung had been happily setting up his own private little kingdom in the North, with the full backing of the Soviet Union. He had built a fully modern and well-trained army, equipped with Soviet weapons, driving Soviet tanks, supported by Soviet planes. When the USA indicated that it was done with South Korea, and with Rhee corrupt, unpopular, and seemingly on shaky ground at home, Kim decideded the time was right, and on June 25, 1950, launched his shiny new army on an invasion of the south.

——–

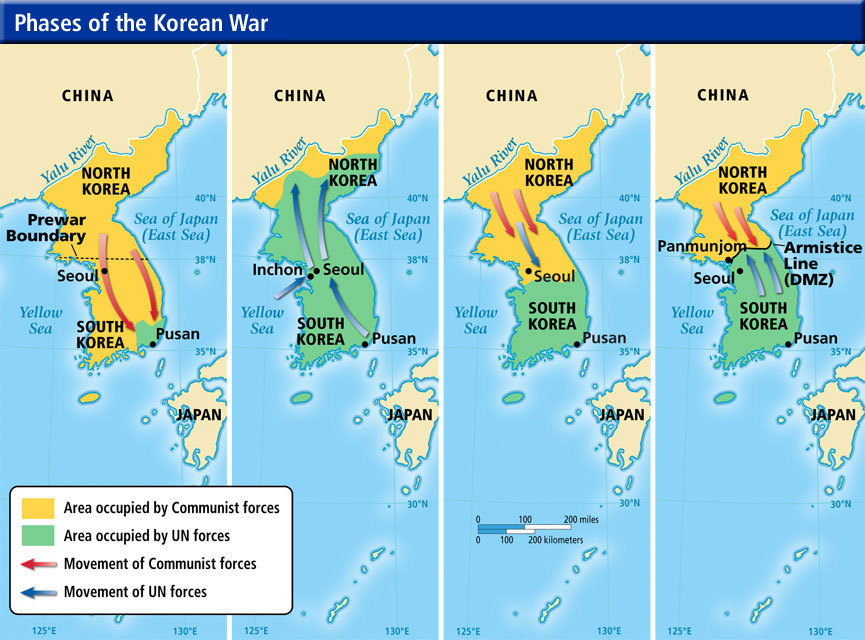

The Korean War is, of course, far too detailed to get into here. Suffice it to say that the United States hadn’t actually meant it was totally done with Korea, and intervened to save its newfound ally. The fighting raged down the peninsula to Busan, and up all the way to the Yalu River, and back again. Seoul changed hands 6 times. The United States carried out the longest retreat in its history, “attacked in a different direction” out of the Chosin Reservoir, and helped mold the South Korean army into a modern, effective fighting force. By the time the dust settled three years later, the battle lines were more or less right at Bonesteel’s 38th parallel and pretty much the entire peninsula lay in ruins. Oh, and Syngman Rhee now had an ironclad grip on power.

Rhee unabashedly engaged in strong-arm and outright illegal political tactics. While he wasn’t as bad as Kim Il-Sung to the north, “not as bad as a literal Stalinist dictatorship” is a very low bar to clear. Opposition parties were harassed, their leaders frequently arrested, and at times politicians who became too prominent in opposition to Rhee were outright assassinated, such as Kim Gu. Under the pretext of resisting subversion from the north** Rhee severely curtailed political rights and elections, limiting the ability of opposition parties to dissent from his regime. At times, his security forces engaged in outright massacres, including an astonishing reported 14,000 deaths during the Jeju Uprising. (Tirman, John (2011). The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America’s Wars. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-19-538121-4. I have not investigated this claim myself).

Through the 1950s, Rhee amended the Constitution as he willed and more or less ignored South Korea’s National Assembly, getting himself elected President 4 times. The United States grumbled over his strongarm tactics, but any instability in Korea risked opening a way for the North to invade. The threat of the North acts as a constant pressure in Korean politics, forcing unity and enabling strongmen to maintain a tight grip on power. Time and again it will be used to justify all manner of authoritarian actions, including, as we will see, in response to the May 18 Uprising. In so doing, Rhee set the model for a Korean dictator that would persevere for 40 years. South Korea was by no means a free state. It was better than the North, yes, but again – low bar. Opposing parties were allowed to exist, but certainly not to win elections. Writing an opposing newspaper might work for a while, but it would eventually get you arrested (but probably not executed). And as long as you kept your head down and ignored politics, you could live a more or less free life.

Rhee’s ride on the tiger finally came to an end in 1960, in what would become another familiar model in Korean politics. In the spring of that year, Rhee staged yet another fraudulent election, and once again, surprise surprise, he was unexpectedly re-elected because he was so beloved by the Korean people as the father of his nation (in fact, Rhee won 100% of the vote after his main opponent died a few weeks before the election. As far as I can tell, the death was actually legitimate and not a shady assassination, surprisingly enough. Go figure). Yet again, people – mostly college and high school students, took to the streets to protest yet another sham election.***

During the protests, in the southern city of Masan, the corpse of a high school student, Kim Ju-yul, was discovered. The regime announced that the boy had drowned, but autopsies revealed that his skull had been fractured by a tear gas grenade fired at point blank range. While the regime had been authoritarian and oppressive, it had never before stooped to the open murder of citizens in the streets. The Korean press widely publicized the incident, and the protests caught fire and spread through the entire country. Rhee proclaimed that it was all the work of communist agents, but the tired excuse worked no longer. Within a month, there were marches of hundreds of thousands in the streets of downtown Seoul, demanding Rhee’s resignation. Violent clashes were common, and it is estimated that more than 180 protestors died in confrontations with the police.

But the heart of the police forces weren’t really in it, and soon they began refusing orders to fire on the protestors, who no longer numbered just college students and dotty old professors but respectable Korean professionals and businessmen, too. Rhee proclaimed martial law, but the soldiers, too (no doubt noticing how badly they were outnumbered by the protestors) also refused to fire on the crowds. Left with no choice, Syngman Rhee resigned on April 26, 1960, and went into exile in sunny Hawaii. Thus ended the reign of the United States’ handpicked ruler of South Korea.

The road to the May 18 Uprising begins here, I think. Rhee came to power as a result of the inattention and lack of preparation by the United States for the role it found itself thrust into in Korea. He was emphatically the wrong man for the job. Even as Japan and Germany evolved into modern, multiparty parliamentary democracies, the Republic of Korea was a sham, ruled by an authoritarian strongman who had nothing but contempt for elections and the will of the “common people.” Rhee legitimately tried to rule wisely and well for Korea, and was constantly fearful of the threat from the north and from communists within, but his lack of respect for democratic norms and his cheerful disregard for human rights set a pattern for Korea that would persist for 30 years following his fall. It was in protest to a similar dictator that would lead to the bloody confrontation in Gwangju, 20 years after the fall of Syngman Rhee.

*”The Empire, long divided, must unite. Long united, must divide.” – Romance of the Three Kingdoms, published centuries ago and describing affairs in the 3rd century. Still true today – this line contains everything you need to know about Chinese history.

**To be fair, for a number of years during and after the war, there were literal Communist guerrillas scattered around the mountains to the South. The threat of invasion from within wasn’t entirely made up by Rhee. He did exaggerate it and exploit it for his own purposes, though.

***It is important to note that while South Korea is not a free nation at this time, it is not comparable to the North – imagine these protests in Pyongyang! There are degrees of freedom, and while I’m being hard on Korea here, I am emphatically not saying that North Korea and South Korea were basically interchangeable. One, while flawed, is definitely better than the other.

Prologue: https://gwangjulikeit.home.blog/2020/05/04/5-18-prologue-the-may-18-national-cemetery/

Chapter Two: [tbd]

One thought on “5.18 Chapter One: The Wrong Man for the Job”