It’s quiet at the May 18 National Cemetery.

Oh, there’s the sound of running water, from the fountains that line the massive pavilion at the center. You can hear the sound of early spring birds on this bright clear day in April. The wind whispers gently through the trees on the hills looking down on the graves. But otherwise…tranquility.

This is a rare thing, in Korea.

In the United States, I think we take quiet for granted. There are places you can go without the sounds of people filling the streets, with no military jets flying overhead, without the constant buzz of moped delivery drivers racing down the streets and sidewalks. Sometimes, late at night, you don’t hear the engine noise, of the noraebangs and clubs blasting their music into the alleyways. The alarms of garage gates and traffic crossings, the deep rumble of bus engines, and the unending chatter and laughter of thousands of people out and about at all times – well, in the USA you can be free of that.

Not so here. I don’t know about the Korean countryside, but in Gwangju, in Cheomdan, my neighborhood, the city does not sleep. Every hour of every day is filled with the noisy business of human life, as people hurry about their work, about their play, about their lives. You get used to it after a while, but you also forget what quiet sounds like.

Unless you come out here, to the cemetery.

It sits outside the city, this place of martyrs. A few miles from the heart of downtown, in the midst of the encircling mountains about Gwangju, a placid garden of serenity has been carved out of the landscape. It sits in a bowl, with most of the tombstones on the hillside (as is the Korean fashion). A few outbuildings and museums surround a massive central plaza, ringed in fountains that sparkle in the springtime sun. There are gardens, and trees, and flowers – not in bloom yet, but soon they will open up and this place will explode into color.

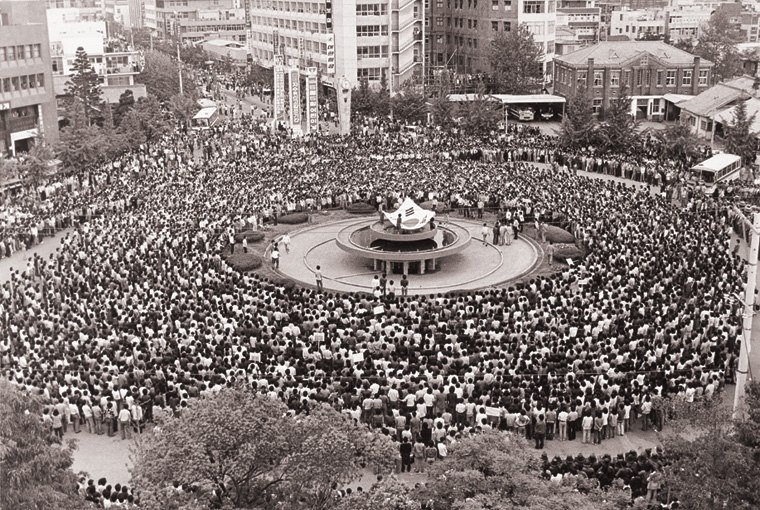

At the center of the plaza stands a large sculpted tower, twin spires gently compassing a bronze torch one hundred and thirty feet above the ground. To either side of the tower are carved reliefs of human figures – people holding signs, building barricades, gathered around a lone speaker standing atop a massive fountain – and some clutching rifles. Nearby is a statue of a jeep, of all things. Around and on the jeep stand more figures in bronze, young people in ordinary clothing, their fists upraised in defiance, flags and rifles held in their hands. Behind, carved messages in Korean English line a stone wall, proclaiming the story of these martyrs.

Beyond that lies the graves.

There are hundreds of them, small barrows standing in neat lines along the hillside. Row upon row they wind back up the hill. They are covered in neatly trimmed grass, most with fresh flowers lying before them. Every barrow – dolmen, they’re called – has a small gravestone in front of it. Printed neatly and humbly in Korean characters is a person’s name, and their place, and time of death. The dates are all similar – mid to late May, 1980. Many have crosses carved into them. Some have bowls of incense in front of them, and some of those are even lit. All are lovingly cared for. But the most powerful part, at least for me, are the photos.

In front of nearly every dolmen there is a photo. Black and white, for the most part. Faces of every age and description smile out from them. Here a young college boy, his goofy grin framed by the long, tousled locks that were the style of the day. There a dignified professor sits in his carefully maintained serenity, in his best suit and his too-large glasses. A middle aged woman with a gentle smile and the calm, sensible hairstyle of her time. Every photo a snapshot of a place and time – Korea, in 1980. Every single one there to remind you that behind this tombstone is a person. A person with their own story, their likes and dislikes. Maybe a boy who had scarcely thought about what he would wear for his school photo that day. Here a young woman caught in the act of laughing with her friends – no official photo. Maybe this is the only one of her that survives? The only record of her left in this world, here, in this quiet little cemetery on this quiet little hill outside the big noisy city.

Some of the graves, of course, have no photos at all. Just a name, perhaps a cross and a date.

They are just as well-cared for as the others.

In total, there are 482 people who rest here. This was not their original location – the military dictatorship that murdered them would never allow such a place of honor for those who died battling their regime. No, this place was established in 1993, following the democratization of Korea. As the new government sought to atone for the sins of the past, the bodies of the honored dead were exhumed and brought out here, to be re-entombed and remembered forever. The entire May 18th National Cemetery stands as a memorial and a museum for those who gave their lives in the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. In Gwangju, it is a famous place.

But not outside Korea, curiously enough. This cemetery, which preserves the mortal remains of more people than were killed in the Tiananmen Square massacre, is virtually unknown in the wider world. The West as a whole knows virtually nothing about the Gwangju Uprising – at least, I did not, and if you will permit me a small moment of egotism, I know a fair bit more about world history than the average Westerner.

I’m not sure why that should be so. Korea itself hails the Uprising as the start on the country’s long road to democracy. At the time, reporters from all over the world gathered here to carry the news from the city to the wider world. But it has since been overshadowed by other revolutions – again, the best parallel I can think of is Tiananmen Square, where pro-democracy protestors were crushed by the Chinese regime. The same happened here, but the protestors were more successful – for a while. And more of them ultimately died.

We forget, I think, because it is inconvenient, sometimes, to remember. It’s inconvenient that a US ally murdered hundreds of its own citizens in order to prop up a tinpot regime that seized power in the midst of a military coup. It’s inconvenient that the troops doing the murdering were there with the tacit approval and active complicity of the United States. At the time, it was easier to accept the regime’s narrative of “riots” and Communist agitators than to court a crisis with a key Cold War bastion, at a time when Russians were invading Afghanistan, when Iran had seized our embassy, and the entire country was undergoing a crisis of confidence. So, in the United States, and by proxy the rest of the West, there is almost no popular memory of a week in Gwangju 40 years ago, a sunny, warm May much like this one, when an entire city threw out a modern, well-trained army and kept them out for days.

I had heard of the story when I came, and memories of the uprising are everywhere around the city, but I didn’t know the details. So, one day, to sate my curiosity, I made my way out here. I would learn, and hey, maybe it would make a good blog post one day. It wound up being much more than that.

The first thing I noticed, of course, was the quiet. That was rare, and it instantly impressed upon me a sense of peace that I hadn’t felt in months. Then, of course, you notice the pillars, and the sculpture. This is not the sort of monument you build to a mere riot.

What struck me most, like I said, was the photos. It is easy, I think, to forget that the names in history books – if they make into history books at all, which most do not – are people. Row upon row, their faces gazed out at me across 40 years. Still young, still with those eyes full of hope, the infectious grins that I’ve seen on young people all over the world – I am young, and my whole life is in front of me, and this is a good time to be alive. College students, mostly, mixed in with their professors and other civilians. Going to school, working towards degrees, towards one day jobs, families of their own. The future. Most of them will always be young, now. Growing old – this is not their fate.

And that was what got me. Because most of these people knew the risks they were taking. They knew that to protest the regime meant death, for many. Not even police dogs and firehoses, not tear gas, but actual bullets and grenades. It would be easy to keep your head down, to not join in, to preserve that entire bright shining future and just get on with your life. But the 482 people here, along with many others – the total numbers of the dead are not known, even today. The total numbers who participated in the uprising can never be known – made the choice to place those futures on the line, to stand up, take their chances, for the simple right to govern themselves.

The same basic impulse that drove colonists in Boston and Virginia 250 years ago, the same that would sweep across the communist nations of Europe 10 years after the uprising – just the simple assertion that I will govern my own life, and no others. It’s a cause worth fighting for, to be sure, and these people did, and backed up their principles with their lives.

And we have forgotten them.

In a few days, it will be the 40th anniversary of the May 18th Gwangju Uprising. The city here is being steadily engulfed in the preparations to mark the occasion. Many Koreans are working hard on art projects, on posters and films, on documentaries and essays and poems, to memorialize the dawn of their democratic movement. But I don’t know much of that will exist in English. There’s actually surprisingly little material in English to work with – a few poorly translated books, vague encyclopedia articles, and outdated (and misinformed) news reports from the time.

Well, let this, then, be my small contribution to the history of Gwangju. I stood in front of the rows upon rows of dolmen, and I promised them that I, at least, would learn their story. And do my best to share it with others. For a brief while, perhaps, these happy young college kids and the ordinary people of 40 years ago can live again. And the sacrifice that they made so that others might live freely can – even if only in a small corner of the Internet – be remembered.

Chapter One: https://gwangjulikeit.home.blog/2020/05/18/5-18-chapter-one-the-thirty-year-prologue/