The six weeks between the assassination of Park Chung-hee and the coup of December 12 were the most uncertain Korea had faced since Syngman Rhee had fled to Hawaii, 20 years before. Then, the faltering and uncertain Second Republic had been overthrown by General Park. Now, the upper reaches of power were split between two men: Jeong Seung-hwa, Army Chief of Staff, and Chun Doo-hwan, head of the Security Command of internal military police. That November saw a short but sharp power struggle between the two generals, “the war of the stars,”* referencing the generals’ stars each wore on their shoulder, to determine the future of Korea.

Jeong Seung-hwa had been offered the presidency by Kim Jae-gyu, the Director of KCIA and assassin of President Park, but instead Jeong had gone to the prime minister, Choi Kyu-hah. Now, under the Yushin Constitution, all power had been invested with the president and the prime minister was mostly useful for keeping seats warm, and accordingly the office was held by a series of non-entities. Prime Minister Choi was another grey and forgettable bureaucrat, or he should have been, but he actually had the temerity to show a spine now that Park was safely six feet under the earth and no longer capable of objecting. Jeung and Choi had collaborated, seen Director Kim arrested, and made noises about possibly, maybe, eventually but not too soon, having real and open democratic elections in the country.

In the other camp was Chun Doo-hwan. This joker had graduated from the academy a few years after Park, and in the wake of Park’s coup, no doubt sniffing which way the wind was blowing, he had led a series of demonstrations in support of the new dictator. Chun’s toadyism was rewarded with a series of military commands, and he even saw shots fired in anger in Vietnam.** Chun led a faction of officers, nicknamed the Hanahoe, “Group of One,” fanatically devoted to Park’s vision of authoritarian rule. Most of the members of this secret club were Chun’s own drinking buddies and cronies from his rise up through the ranks. By 1979, despite the best efforts of KCIA Director Kim (who trusted Chun about as much as he trusted North Korean promises of peace and reconciliation if the South would just see the light on Communism), Chun was in command of the Security Command , one of the quietly most powerful positions in the army due to its role of policing the army and preventing coups. In theory, Security Command was checked by the KCIA, which was also in charge of preventing coups, but in the wake of the assassination Chun had arrested Kim and seized power over that agency, too. It was an extremely dangerous situation for the Republic, one that Choi and Jeong were not blind to.

Like I said, Joeng had made noises about “the Yushin system must end,” and had moved to exclude “politically minded” officers from positions of power. He steadily worked his way through the ranks, re-assigning or demoting officers he considered insufficiently reliable, while Choi attempted to actually move towards becoming something like a leader for the country. Choi won provisional elections on December 6, 1979, to finish out Park’s term, and Jeong felt secure enough to move against Chun himself. Two days later, on December 8, he quietly spoke with the Minister of Defense about getting Chun reassigned to the Eastern Coast Guard command, a safely backwater assignment if there ever was one.

Rumors reached Chun of his upcoming free trip to the chilly Taebaek mountains, and surprisingly he did not react well to the prospect of being exiled from the wealth and power of Seoul to the frozen, rugged shoreline to the east. With his strong power base in the city, he moved quickly. He immediately spoke with a key division head and made a completely plausible-and-definitely-not-made-up-on-the-spot case why Jeong was clearly mad with power and needed to be arrested:

1)He had been friendly with Kim Jae-gyu, the presidential assassin (highly suspicious if you ask me)***

2)He had been “present” at Park’s assassination (in that yes, he was in the general neighborhood)

3)He had received money from Kim at one point (imagine the KCIA clandestinely spending money)

4)He had recommended that some of Kim’s murder charges be reduced (covering for his buddy, eh?)

5)he had asked that the murder trial be quickly concluded, if possible (trying to subvert the wheels of justice, eh? Well, they may grind fine, but they grind slowly, buddy, and you’ll sit there and like it, by Buddha)

6)Also some of the officers just plain didn’t like him (no I am not kidding this was seriously proposed as a reason for the arrest of the Chief of Staff of the entire Korean army).

With these facts laid out in front of him, presumably accompanied by lots of suggestive eyebrow waggling, the 9th Division commander agreed that it only made sense to arrest Jeong. The date was set for December 12. In the meantime, Chun went to his buddies in the Hanahoe and quickly recruited their support for his scheme. Through his friendship with park, most of the upper ranks of the military were seeded with his supporters, and he could pull upon several combat divisions, paratroop brigades, and capital guards for his plot.

On the appointed day, Chun and a couple flunkies entered army headquarters using the pre-arranged password “A birthday party in the house,” and got the festivities started. Two officers hurried to Jeong’s residence, arriving just before 7, where they unaccountably faffed about for 25 minutes before getting around to telling Jeong that they had a presidential order to arrest him to record his “statement concerning Kim Jae-gyu.” Jeong inexplicably grew upset at this and demanded to speak to the president personally about this arrest order, which as you can imagine would have been super awkward since of course President Choi had made no such order (and in fact hadn’t yet even been informed of the arrest in progress). When the officers refused, Jeong called his aide into the room with some of his guards. A short but sharp firefight broke out between the arresting squad and Jeong’s reinforcements, and Jeong’s aide was killed. The conspirators were victorious when one of their squad, no doubt incredibly excited to act out a scenario he’d rehearsed many times in his head during the long hours of boring guard duty, blasted his M16 through a window before crashing through himself to get the drop on General Jeong. Jeong was taken into custody.

Meanwhile, Chun and some other bigwigs headed to President Choi’s official residence and got around to asking permission to arrest Jeong. And here their troubles began: Choi refused to grant that permission. That made matters a tad delicate, since of course the conspirators had already gone ahead and done the thing. Choi argued that such a move needed the consent of the defense minister. Chun pleaded and persisted, but the Official Chair-warmer had grown into his role as President and held out, demanding to see the minister. He also ordered Chun to return to his post. Chun shrugged and casually ordered his men to disarm the presidential guard and blockade the President in his home until he saw reason.

He rounded up some reinforcements – impressive looking military commanders, a handful of privates with big guns to look intimidating, and then stormed back into the President’s office to try and strongarm him into legitimizing hte arrest, claiming that all the senior military officers (look, I went to a lot of time and effort to round up all these generals and colonels and you will respect that!) were behind him. Unaccountably, Choi’s backbone held, even with the guns being waved around in his office, and he still refused. Chun Doo-hwan was now in a very awkward position of his own making. He couldn’t exactly un-arrest Jeong, but to persist would make him guilty of mutiny. His attempt to neutralize General Jeong would have to escalate to a full-blown coup.

Around the capital, other members of the military were catching wind of the situation. Jeong’s deputy, Vice-Chief of Staff Yun Seong-min ordered Chun and his cohorts to return to their posts, and while they were at it to release his boss. Chun ignored him. Officers around Seoul started to hurry to their posts.

By 10:30, more than 3 hours of bluster had failed to sway Choi. In desperation, the coup leaders knuckled under to his demands and phoned the Defense Minister, asking him to come over, hoping – I guess? – that he would legitimize their move. The Defense Minister hadn’t been born yesterday, despite Chun’s assumptions, and refused to come, instead saying that Jeong had to be released. At that point, Chun concluded approximately, “Fuck it,” and ordered in the paratroopers.

The conspirators’ armed muscle flooded into the streets as the clock turned to December 13, and quickly seized most of the key military headquarters and took everyone who wasn’t on board with the program into custody. By dawn the citizens of Seoul woke up to tanks in the streets and Chun Doo-hwan firmly in control of the levers of government. He and his buddies, showing the imagination military officers are famous for, began styling themselves the New Military Power. The entire coup had taken only about 10 hours from start to finish.

Or had it?

In later years, historians would call this the slowest coup in recorded history. It took more than 8 months for Chun to secure power, because there was an unexpected snag in hsi plan: Fucking Choi had a backbone.

Choi had just been elected president, and actually commanded some level of popular support, more or less. Furthermore, the illusion of the Republic of Korea as a democracy was critical to maintaining the vital alliance with the United States. So while Jeong was neatly squirreled away in a prison for his role in the assassination of President Park****, Chun couldn’t just arrest or shoot Choi out of hand.

It wasn’t that Choi actually mattered. The entire country was under martial law, and Chun was effectively running things. But without Choi, Chun lacked any sort of legitimacy, and he needed that legitimacy to stabilize his rule. As long as Choi held out, Chun’s regime teetered atop a volcano of public protest and outrage. So, Chun worked quietly to undermine and sideline Choi, until he could be neatly placed aside.

The New Military Power worked all through that winter and spring to consolidate the new regime, the 5th Republic.***** The army’s information warfare section was expanded and initiated “K-Operations,” a policy aimed at suppressing the public’s desire for democratization and increasing their desire for safety, playing up the North Korean threat and the threat from internal subversion. Another, more significant measure was “True Heart” training.

Chun had seen what a friggin’ mess of things college students could make, if given the opportunity, and he was sick to death of the kid glove tactics the police employed that let things get out of hand. He hated images of long lines of police standing around with their thumbs in their belts while idiot college kids burned down the city. If he’d been in charge there would have been no Bu-Ma protests, no sir! Hell, there wouldn’t have been an April Revolution, like the one that brought down President Rhee. Chun would avoid their mistakes.

He took his most reliable troops, the paratrooper brigades that had won him the capital, and started training them in new counter-protest tactics. These new skullbreakers were taught to charge in and aggressively break up demonstrations. They’d punch the protestors right in the mouth and then kick their asses again as they ran off home. The True Heart units would harass and continually break up new groups of protestors, take ringleaders into custody, and prevent any mass movement from organizing. They were given swanky new batons, ash, about 70 centimeters long, and fully capable of bashing in the head of some Physics major from Seoul University with a minimum of fuss. Any demonstrators they caught would be stripped, tossed in a truck, and shipped off to a prison to be roughed up for a few more days before they were turned loose, having learned a very valuable lesson about Respect For Authority.

There was a certain sense of urgency around the True Heart program, since Chun had a lot of angry Physics majors in the streets in those days.

Students had long been a source of headaches for which ever authoritarian regime was the latest to slouch into Seoul. Rhee had been toppled by protests over the death of a student, and the little brats had been such a headache for Park that in 1975 he banned student organizations altogether and imposed his own program, the Student Defense Corps. That had gone by the wayside with his death, though, and the next generation began to once again slink back out onto the streets.

Tentatively, starting around April in Seoul and then spreading to other universities nationwide, the students started such radical measures as having Student Council elections and suggesting that perhaps all male college students shouldn’t be required to give several years of their lives to the military. The New Military Regime denounced this behavior as obviously unpatriotic and said that the students “lacked security consciousness,” since clearly the thin blue line of drafted gawky teenagers was the only thing holding back the ravening hordes of Communist supermen to the North. Confrontations and clashes between the kids and the military became increasingly common.

The students tried to avoid criticisms that they were “destablizing” the country and opening a window for an invasion by limiting their protests mostly to campus. But at the same time, their demands grew from the modest request that they be allowed to elect their own student governments to full blown demands for the democratization of the country. Choi still refused to give his assent to the New Military Regime, and that refusal fueled the students. The protests spread and became general in universities across the country as April turned to May.

It was a time of hope for the students. Choi still talked about democracy. For many of them, it was the first time in their lives they had known any regime except that of Park Chung-hee. Anything seemed possible – even a democratic future for Korea. They started calling it the “Seoul Spring,” in memory of another hopeful springtime twelve years before, in Prague, 1968.

Of course, that spring had ended bloodily.

The protesters demanded an end to martial law and that power be rested from the hands of Director Chun (who had, in the meantime, resigned from the army so that he could be appointed director of the KCIA, now reformed in his image). And all the while various units completed True Heart training and were quietly spread around the country.

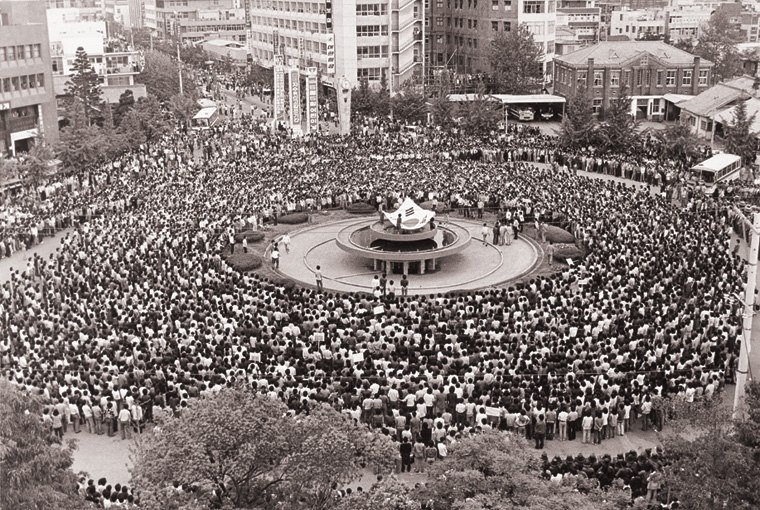

The first two weeks of May saw things rapidly approaching a climax. 27 student groups from universities across Seoul met quietly, and then returned to their campuses with a unified plan of action. 70,000 students poured into the streets (I know, I can hardly believe it, either – students who pay attention to their student council!), marching and chanting slogans calling for the downfall of Chun and the ‘remnants of the Yushin system.’ The next day, May 15, 100,000 students joined – and the protests were going nationwide. Every city with a major university saw students surging into the streets.

However, the general population was reluctant to join in. With no popular support, the students for once in their lives did the prudent thing and toned things down. May 16 and 17 were quiet, mostly, as the students quietly withdraw and plotted their next move in their ongoing confrontation with Chun.

And it was here that Chun completely screwed the pooch. After more than 6 months of wrangling, he had had it with Choi’s continued refusal to get with the program. The growing flame of the student movement finally ran out his patience. At an emergency meeting on May 17, he and his cronies in the New Military Power sat down with ‘president’ Choi. Demonstrating the growing unrest in the streets, Chun browbeat Choi into accepting an extension of martial law: Now campuses, too, after their brief flirtation of freedom following the Park assassination, would be firmly placed under the control of the military. True Heart units were even then en route to every university in Seoul, as well as detachments sent to major universities in the provinces. The universities would be closed until all that could be sorted out, the ringleaders of the little jerks in the streets would be arrested, oh, as would most of the ringleaders of the political opposition in the National Assembly, who had been gleefully making hay of the whole situation. Oh, and Chun was fed up with Choi’s antics: He would resign as soon as things calmed down and Chun would become president.

Satisfied, Chun left the meeting, which had been effectively a legal coup. The longest coup in the history of the world, stretching from December 12, 1979 to May 18, 1980, was over. He went to bed that night satisfied that he cut the head off the student movement, that his True Heart units would mop up any lingering dead-enders, and his political opposition was effectively neutered.

When he woke up, he learned that some jokers down in Gwangju apparently hadn’t gotten the memo.

*Not to be confused with “the Star War,” which I believe is a popular science-fiction franchise created by George Lucas.

**After the United States, Korea had the second-largest commitment of troups to the defense of South Vietnam, more than 300,000 men. They accomplished little beyond padding the pockets of a gaggle of corrupt REMFs and depopulating several backwater provinces, but in fairness that’s about all the Americans managed anyway so we can’t be too harsh on them.

***Somehow Chun delivered this briefing with a straight face, despite the fact that Kim Jae-gyu had literally offered Jeong the Presidency already and Jeong had turned it down, and that it had been Jeong himself who ordered Chun to investigate and arrest (not necessarily in that order) Director Kim.

****He would at last be released 17 years later and cleared of all charges. Jeong passed away in 2002.

***** Syngman Rhee had led the First Republic. The Second had been the brief-lived liberal regime before Park’s coup. Park had led the Third Republic, then after proclaiming the Yushin Constitution the Fourth.